Chemical oligonucleotide synthesis is performed as a stepwise, solid-phase synthesis. Because each step involves the formation of a new chemical bond, each nucleotide can only be added with 100% regio- and stereochemical accuracy if all the functional groups not involved in the desired chemistry are protected with orthogonal protecting groups. Thus, protected nucleoside monomers are, in essence, inert building blocks that can be activated for coupling only at the point of addition to prevent any branching, base modification or phosphate isomerization that would otherwise destroy sequence fidelity and purity. If unprotected, the many nucleophilic and acidic groups on the sugar, base and phosphate would be free to engage in numerous competitive side reactions, leading to truncated and/or mutated chains and precluding commercial-scale synthesis.

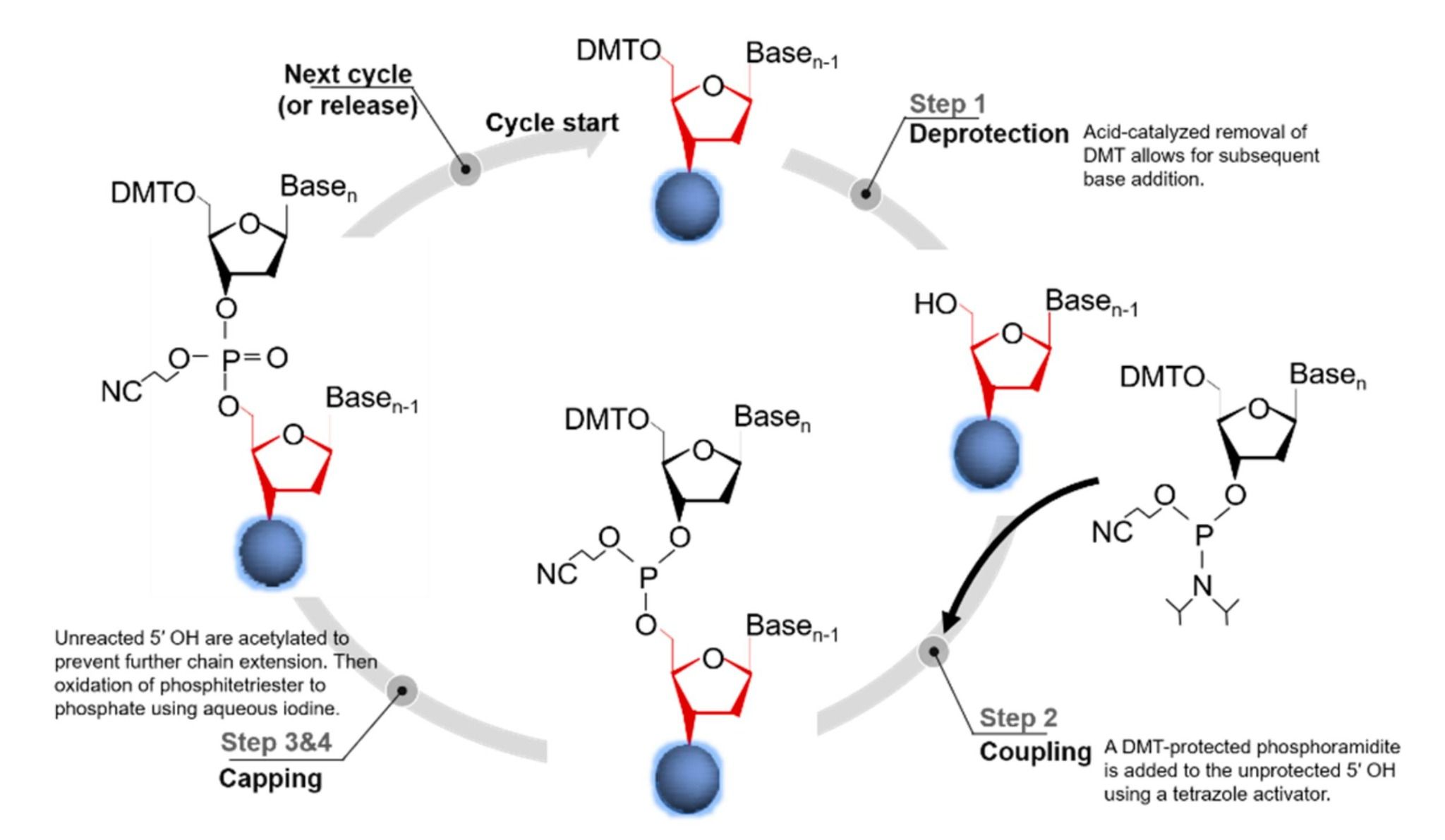

Fig. 1 Phosphoramidite-based oligonucleotide synthesis.1,5

Fig. 1 Phosphoramidite-based oligonucleotide synthesis.1,5

Coupling an oligonucleotide on a solid support to give a single-stranded DNA or RNA requires that each coupling step be quantitative and site-selective, with all the other hydroxyls, amines, and phosphate oxygens being chemically inert. The repetitive nature of this sequence and use of acidic activators, oxidants, and nucleophiles makes oligonucleotide synthesis prone to damage to unprotected residues, introduction of errors, and decreased overall yield. Protecting-group chemistry is not a scholarly nicety but an engineering requirement at the heart of the phosphoramidite method.

Each nucleoside has at least four potential reaction sites, or centers of reactivity: the 5'- and 3'-hydroxyls of the sugar, the exocyclic amines on A, C and G, and the phosphate or phosphite triester that is made during the coupling step. Unless protected, any of these may become the subject of acid-catalyzed depurination, transamidation or phosphoryl migration, particularly after the repeated dichloroacetic acid treatment steps used for 5'-detritylation. Orthogonal masking (acid-labile DMT for the 5'-OH, acyl or amidine for the base amines, β-cyanoethyl for the phosphate) means that only the desired 3'-phosphoramidite center is vulnerable to tetrazole activation, preserving base integrity and chain directionality through the cycle.

Solid-phase elongation with unprotected nucleosides results in immediate cross-linking: the 5'-OH on the growing chain can attack several incoming phosphoramidites and, during capping, the bases amines are also acylated in an undesirable side reaction. The result is a set of truncated or branched sequences that elute from the HPLC column at the same retention time as the full-length product. The crude product mixture must then be purified by extensive chromatography which, not only reduces stepwise yield, but also often does not meet final specifications for purity and identity. Protection effectively turns an intrinsically unruly polyfunctional molecule into a single-reaction synthon, allowing the high coupling efficiencies required in commercial oligonucleotide synthesis.

Orthogonal protecting groups serve as programmable opening/closing gates that only open in a precisely timed sequence. Acid removes the 5'-DMT gate to expose the coupling site, mild base later opens the base- and phosphate-protecting arms during global deprotection, and finally fluoride or ammonia opens the gate to release the native nucleic acid. Temporal control allows automated synthesizers to cycle detritylation, coupling, capping and oxidation hundreds of times without cumulative damage, ensuring each nucleotide added is in correct orientation and the strand can be released from solid support with minimal chemical scar. In short, protection chemistry is the enabling language that translates molecular biology's digital code into reliable, manufacturable therapeutics and diagnostics.

Table 1 Protecting-group duties in phosphoramidite synthesis

| Functional Site | Protecting Group | Purpose | Cleavage Condition |

| 5'-OH | DMT (dimethoxytrityl) | Blocks premature elongation | Mild acid (DCA/TCA) |

| Base amines (A, C, G) | Benzoyl / isobutyryl | Prevents base acylation | Aqueous ammonia |

| Phosphate | β-cyanoethyl | Stabilizes phosphite triester | Concentrated ammonia |

| 2'-OH (RNA) | TBDMS or TOM | Avoids 2'→3' migration | Fluoride ion or acid |

Oligonucleotide synthesis is only possible because each nucleoside bears several nucleophilic or acidic sites that would otherwise cross-react during iterative coupling, capping and oxidation. The functional groups—the exocyclic amines on the bases, the hydroxyls at multiple sugar positions, and transient phosphite centers—must be masked with orthogonal protecting ensembles so that only the 3'-phosphoramidite is exposed for tetrazole activation. Failure to shield even one of these motifs triggers branching, depurination or phosphate isomerization that propagates exponentially along the chain and collapses final purity.

A competing and unprotectable nucleophilic amine group is present in adenine, cytosine and guanine, leading to direct acylation by activated phosphoramidite in the absence of efficient oxymethylation of the 5'-hydroxyl group. The acylation by capping or transamidation under basic conditions (deprotection) yields base-modified adducts that co-elute with the full-length strand. Base-labile amide masks (benzoyl for A and C, isobutyryl or dimethylformamidine for G) are therefore installed before phosphitylation and left in place during chain assembly to ensure that only the desired hydroxyl chemistry can take place, while the heterocyclic core is left unaltered until global ammonia cleavage.

The 5'-primary hydroxyl is transiently masked to ensure 3'→5' directionality; the acid labile 4,4'-dimethoxytrityl (DMT) ether is removed at the start of each cycle, freeing the only nucleophile which will attack the next incoming monomer. RNA substrates have an additional 2'-hydroxyl whose nucleophilicity would otherwise cause intramolecular transesterification; this centre is protected by fluoride labile silyl ethers such as TBDMS or TOM that are resistant to all iterative acids and bases but are removed under mild fluoride conditions during final deprotection. By deactivating all hydroxyls except the 3'-phosphoramidite, the sugar scaffold is preserved intact but repeatedly available for high-yield couplings.

A mixture of free amines and hydroxyls would set up a competition where activated phosphoramidite could be "captured" by more than one site. The resulting branched or truncated products cannot be separated cost-effectively. Orthogonal protection unblocks these road-blocks, by matching the kinetics of deprotection to the four-step cycle: DMT leaves in seconds under protic acid conditions, amide protecting groups last days under the same conditions, and silyl ethers are untouched until deliberate exposure to fluoride. This timing ensures that each nucleotide is added as a unit and extends only in one direction, while the overall accumulation of protecting groups protects the entire chain from acid-catalyzed depurination or base-promoted phosphate migration until a global deprotection step liberates the native nucleic acid.

In practical terms, a successful synthesis is less a chain of reactions than a precisely choreographed sequence of masking and unmasking events. The approach is based on an orthogonal ensemble whose deprotection windows do not overlap: acid-labile ethers for 5'-OH, base-stable amides for nucleobase amines, fluoride-cleavable silyls for 2'-OH, and a phosphate cloak that withstands everything until the final ammonia bath. Each group must also withstand repeated cycles of tetrazole activation, iodine oxidation and capping, and then vanish without trace when its turn to go comes, leaving no chemical scar that could mutate the strand or poison the catalyst. The following sections dissect the three key pillars – orthogonality, robustness under cycle stress, and compatibility with solid-phase logistics – on which the decision whether a protecting suite will scale or collapse under plant conditions turns.

Orthogonality refers to the ability of the cleavage conditions of one protecting group to not affect any of the other masks that remain required downstream. The 5'-dimethoxytrityl ether is cleaved using a brief exposure to an acid whose pH and residence time are carefully titrated to be too weak to hydrolyse the base- or phosphate-protecting arms; conversely, the concentrated ammonia used to cleave base amides and phosphate β-cyanoethyl groups leave silyl ethers intact, so a later fluoride step can be used to deprotect the RNA 2'-hydroxyls without causing depurination. This kinetic windowing is confirmed by forced-spiking studies in which each deprotection reagent is deliberately overdosed to confirm that off-target cleavage does not go beyond the threshold for genotoxic impurities. A lack of strict orthogonality leads to premature deprotection, loss of bases or phosphate migration that gives rise to truncated or branched sequences that cannot be economically purged.

Each protecting group must survive dozens of cycles of tetrazole phosphoramidite activation, pyridine-acetic anhydride capping and iodine oxidation, which together impose a sufficiently broad redox and pH range to hydrolyse ordinary esters or carbamates. Base-protecting amides therefore require electron-withdrawing substituents to increase the hydrolytic activation energy, while silyl ethers require sterically demanding alkyl substituents to shield the silicon-oxygen bond from protonation. Stability is verified by accelerated ageing: crude reaction mixtures are stored at high temperature for prolonged periods, then analysed for the presence of new peaks that would indicate partial deprotection or isomerisation. Routes that display even marginal drift are redesigned—either by changing to more robust masks or by reducing the exposure times—before the chemistry is frozen in a validated control strategy.

Solid-phase operation also introduces mechanical considerations rarely faced by solution chemists: solvents must dissolve the protected monomer, but also swell the resin, filtration times must be on the order of minutes or less to maintain short cycle times, and all reagents must be removable via simple washing without chromatography. As a consequence, protecting groups must be lipophilic enough to provide good organic solubility, but polar enough to not leach into non-swelling wash solvents. In addition, acid-labile masks must cleave quickly at room temperature to avoid resin dehydration, while base-stable groups must be resistant to the mildly alkaline conditions applied for oxidation. These competing requirements are balanced by iterative Design-of-Experiments: resin swelling, flow rate and temperature are varied in concert to find an operating window in which deprotection kinetics remain first-order and coupling efficiency remains above the acceptance threshold across the entire column volume.

Selecting an appropriate protecting scheme is by far the most important decision in the design of a phosphoramidite method. Protecting groups must (i) tolerate multiple exposures to acids, bases and oxidants, (ii) leave no mutagenic residues after global deprotection and (iii) conform to existing plant effluent regulations. The current list is therefore divided into three conceptual levels: base-labile amides for nucleobase amines, acid-labile ethers for 5'-OH, and fluoride-labile silyls for 2'-OH. Expertise in their relative windows of lability determines if a multi-kilogram synthesis proceeds with predictably clean purges or devolves into a chromatographic horror show.

Exocyclic amino functions of A, C and G are converted into nucleophilicity-suppressing carboxamides that do not perturb base-pairing geometry. Benzoyl (Bz) is the historic default for A and C, in part because it affords crystallinity and a clean UV signature, whereas the more bulky isobutyryl (iBu) group protects the N2 of G from unreacted O6-alkylation side reactions. More labile masks—phenoxyacetyl (PAC) or 4-isopropylphenoxyacetyl—permit ultrafast ammonolysis at room temperature, an advantage if the oligonucleotide bears base-sensitive conjugates. The choice among these must balance three tensions: (a) the amide must survive longer than the cumulative acid exposure of all coupling cycles, (b) the cleavage rate must be fast enough to keep the factory floor time below practical limits, and (c) the released carboxylate must not precipitate inside the synthesis column. A side-by-side spiking study comparing PAC vs Bz under identical deprotection clocks often reveals that the milder mask reduces N-glycosidic hydrolysis by an order of magnitude, translating directly into higher full-length yield after ion-exchange purification.

The 5'-hydroxyl is temporarily protected by the intensely orange 4,4'-dimethoxytrityl (DMT) ether whose carbocationic chromophore also serves as an on-line coupling monitor. Its lipophilicity also helps resin swelling and its cleavage window (≈2 % dichloroacetic acid, seconds) is just narrow enough to leave base and phosphate amides intact. For RNA, the 2'-OH adds a second layer of complexity: tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBDMS) is still the work-horse, being robust to oxidation and capping, but which cleaves away in minutes when treated with a fluoride ion. The more sterically encumbering tri-isopropylsilyloxymethyl (TOM) group has even higher acid stability, which is an advantage when ultra-long sequences require long detritylation soaks. A common trap is mis-matched steric bulk, with over-silylation slowing phosphitylation kinetics, and under-silylation leading to 2'→3' isomerisation when exposed to ammonia for too long. Screening therefore combines kinetic phosphitylation assays with forced-degradation HPLC to ensure that the chosen silyl ensemble not only maintains coupling efficiency above the validated threshold but also that it does not introduce any new late-eluting impurities.

Temporary protecting groups are deinstalled within the synthetic cycle itself, while permanent ones survive until global cleavage. DMT is the quintessential temporary group: its sole function is to gate the 5'-OH during a single coupling event, and then it is discarded to unveil the next reactive site. Permanent groups (base amides, 2'-silyls, phosphate β-cyanoethyls) withstand dozens of acid/base insults, and are only removed once the full-length product has been cleaved from the resin. Mistakes are expensive: installing a "permanent" amide that is in fact labile under oxidation conditions results in gradual base deprotection, buildup of deletion mutants and loss of purity specifications. The other extreme, not removing a "temporary" DMT through an ammonia wash, would cap the 5'-end irreversibly, and prevent further extension. A pragmatic qualification protocol therefore subjects each protecting arm to a three-stress matrix (extended acid, higher oxidation temperature, concentrated ammonia) to ensure that its lability class is consistent with the intended temporal role before the route is frozen under change-control.

Protected nucleosides are first converted to 3'-O-phosphoramidites to provide the activated monomers used as feedstock for solid-phase synthesizers; the coupling of base, sugar and phosphate protection to a P(III) amidite handle provides a single-reaction synthon that is stable under inert atmosphere but will couple in seconds with tetrazole activation. It is this transformation that links classical carbohydrate chemistry to contemporary oligonucleotide synthesis, because it converts a multi-functional nucleoside into a building block in which the only reactive centre is the 3'-phosphoramidite, thus permitting iterative, high-yield chain extension without chromatographic separation between cycles.

The synthetic route is initiated by exhaustive protection of the nucleoside: base-labile amides (benzoyl, isobutyryl) protect exocyclic amines, acid-labile DMT protects 5'-OH and TBDMS or TOM silyl groups protect the 2'-OH of RNA substrates. The fully protected nucleoside is then reacted with a phosphitylating reagent, usually a chloro- or cyanoethyl-phosphoramidite, in the presence of a mild base to install the 3'-O-diisopropylamino phosphoramidite function. This reaction must be performed in strictly anhydrous conditions because residual water hydrolyses the P(III) centre; work-up involves filtration through neutral alumina or silica to remove salts, then precipitation or crystallisation to give a stable white solid that can be stored under argon for months. The robustness of the route is gauged by the anomeric purity of the final amidite, as any 2'-regioisomer or residual 3'-H nucleoside is a chain-terminating impurity during solid-phase elongation.

Each cycle begins with an acid-mediated detritylation, which unveils the 5'-OH of the elongating chain. The protected phosphoramidite for the next nucleotide is then activated using tetrazole to generate a reactive P(III) intermediate, which is coupled to the free hydroxyl group in a few seconds. Acetic anhydride is used to cap unreacted chains, and the nascent phosphite triester is then oxidised to the more stable phosphate triester using iodine. The cycle can then begin again. The use of protecting groups ensures that each functional group, except the 3'-amidite, is masked and so side reactions, for example base acylation or 2'→3' phosphoryl migration, are minimized. It is possible to repeat the cycle thirty or more times with little cumulative damage to the growing chain. The whole sequence is automated, but its success is due to the chemical inactivity of the protecting groups used to mask the nucleobase, sugar and phosphate until the final global deprotection.

Reaction efficiency is usually not limited by the reactivity of the phosphoramidite but by the properties of its protecting groups. The 2'-silyl group can sterically hinder the reaction of the activated P(III) with the 5'-OH group, while too lipophilic a base amide may cause precipitation in anhydrous acetonitrile. This causes incomplete mixing of reagents and local under-coupling. On the other hand, if the base mask is too labile it will detach partially during oxidation to give free amine, which will consume activated monomer through a side reaction of amine acylation. The resulting effect will be reduced stepwise yield. Therefore an optimum has to be found by balancing steric bulk and solubility (amide is less bulky than ester), and lability (e.g. TOM rather than TBDMS for RNA, avoiding moisture which would hydrolyze the amidite). When these are properly adjusted, the resulting average step yields are higher than the reported required limits, and the yield of full-length oligonucleotides will match commercial quality standards without the need for preparative HPLC of the crude oligonucleotide.

Table 2 Phosphoramidite cycle and protecting-group duties

| Cycle Step | Chemical Event | Protecting Role | Risk if Mask Fails |

| Detritylation | Acid exposure | 5'-DMT only | Premature loss → branching |

| Coupling | Tetrazole activation | All others stay on | Base deprotection → acylation |

| Capping | Ac2O/Pyridine | Amines remain masked | Free NH2 → chain termination |

| Oxidation | I2/H2O/Pyridine | Phosphate mask endures | β-CE loss → diester hydrolysis |

Upscaling a protected nucleoside from gram-scale route scouting to multi-ton oligonucleotide campaigns requires early convergence of chemical, engineering and supply-chain logic. The protecting groups that provide orthogonality in the lab also bring with them failure modes - moisture-catalysed deacylation, acid-mediated depurination, metal-promoted silyl migration - that become exponentially expensive to manage once 10 kL reactors and continuous-flow phosphitylation skids are brought on line. Successful scale-up therefore treats the protected nucleoside as a pseudo-pharmaceutical intermediate, whose stability envelope, impurity fate and handling protocol are put under cGMP change-control before the first GLP tox batch is made.

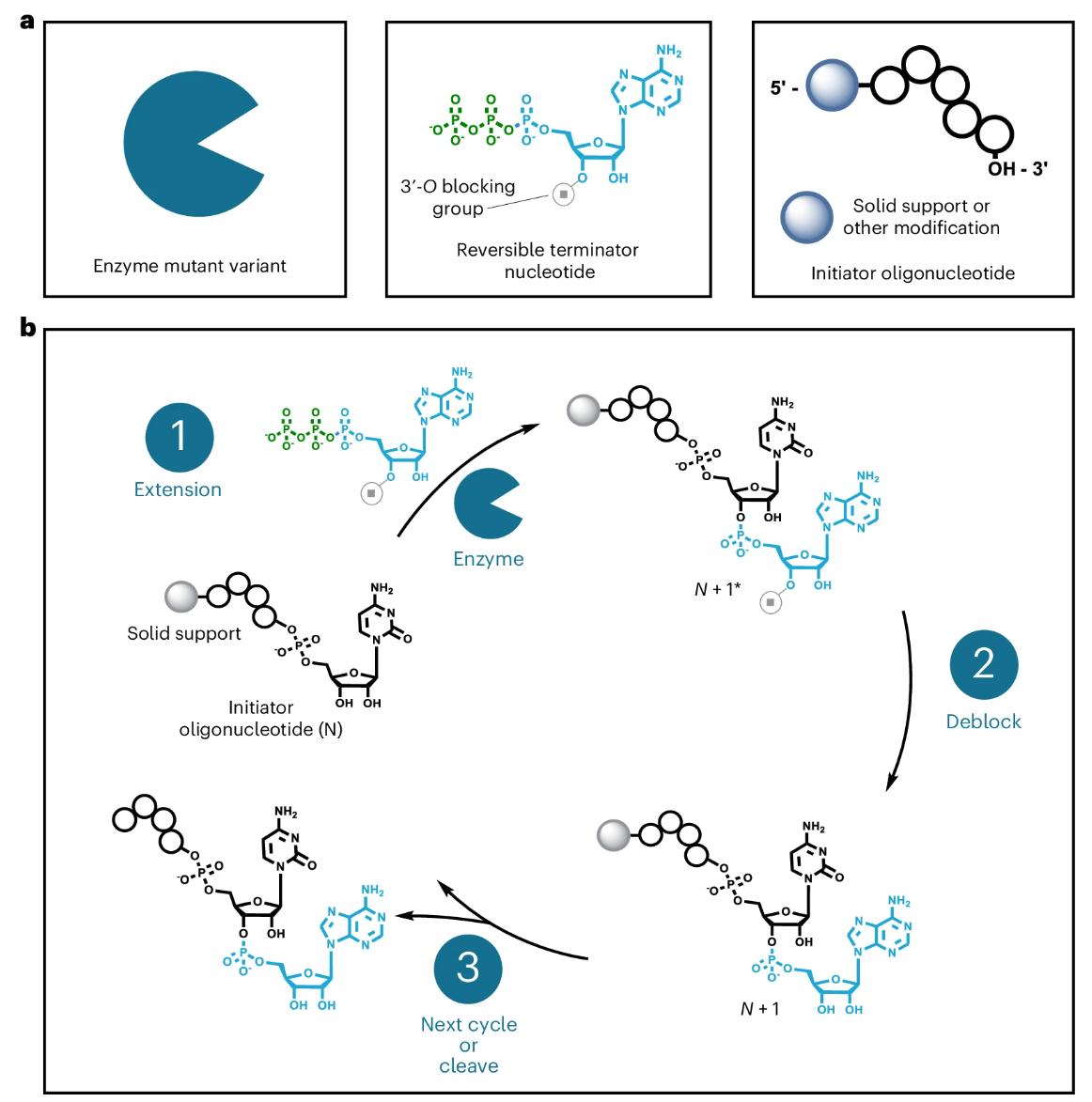

Fig. 2 General overview of the controlled, template-independent enzymatic RNA oligonucleotide synthesis process.2,5

Fig. 2 General overview of the controlled, template-independent enzymatic RNA oligonucleotide synthesis process.2,5

Protected nucleosides need to be able to withstand several months of warehouse drift with no detectable loss of protecting-group integrity. Amide masks hydrolyze slowly in ambient humidity, silyl ethers can migrate on exposure to trace amounts of acid vapors from neighboring cartons, and phosphate β-cyanoethyl groups can undergo premature elimination if exposed to light or high temperature. A proper stability protocol therefore needs to encompass both long-term, refrigerated storage and in-use exposure once the drum is opened under plant humidity. Packaging is qualified in alu-laminated pouches back-flushed with argon, and desiccant sachets are added to ensure water activity does not exceed the critical threshold as defined by forced-degradation studies. Any excursion—temperature spike during trans-shipment, pin-hole in the foil seal—activates a re-test calendar that links residual moisture content to protecting-group loss kinetics, ensuring that only material that is within its validated stability window is used in the phosphoramidite plant.

Phosphoramidite is not the only moisture-sensitive moiety: base-protecting amides can also hydrolyze, to free amines that later act as chain-terminating impurities in solid-phase elongation. Handling is thus factory-protocol equivalent to semiconductor clean-room practice: unsealing drums in a glove-box enclosure held at low dew-point, and then in-house time limits (typically reported in "open-hood hours") are confirmed by on-line Karl-Fischer profiling. Transfer lines are stainless-steel with PTFE gaskets to eliminate metal-catalyzed silyl cleavage, and pneumatic conveyance uses dried nitrogen rather than plant air to avoid adiabatic condensation of moisture. Operators wear low-lint gloves, since residual cotton fibers can contain sufficient atmospheric water to elevate the bulk moisture above the validated ceiling once the powder is dissolved in anhydrous acetonitrile. These precautions are recorded in the batch record as critical process parameters; any deviation mandates an immediate hold until re-analysis confirms that protecting-group integrity is within specification.

Scale-up, however, will dramatically magnify trace impurities that were chromatographically invisible at the gram scale. A 0.1 % w/w base-deprotection side product can amass in mother liquors, seed crystallization filters and ultimately co-precipitate with the final amidite, forcing costly re-work campaigns. The control strategy therefore begins with a route-specific impurity fate map: each synthetic intermediate is spiked into pilot batches to demonstrate purge through crystallization, washing or carbon treatment. Analytical packages employ orthogonal separations—ion-pair HPLC for polar impurities, gradient GC for residual solvents, ICP-MS for metals introduced during filter-aid addition—to ensure that no new peak emerges above the genotoxic qualification threshold. Reference standards are prepared from batches that have undergone accelerated degradation, so that future lots are judged against a library of authentic stress markers rather than hypothetical structures. Finally, statistical process control tracks the ratio of key impurities to main peak area across consecutive campaigns; a drifting trend is investigated as a potential precursor to failed downstream coupling efficiency, allowing corrective action before the material reaches the oligonucleotide synthesis suite.

Truncating the protecting-group strategy does not just reduce yield; it short-circuits the synthetic landscape. Exposed amines (bases) alkylate phosphites; unprotected sugars (missing 2'-masks) cyclise to phosphates; acid-labile groups (tags) cleave during oxidative work-up. The mutant soup that emerges has mutational burdens that evade standard analytics and reveal themselves only when clinical-grade purity cannot be obtained.

An unmasked cytosine N4 attacks the activated phosphoramidite, making a stable phosphonamidate that terminates elongation and creates a pool of (n-1) strands. A naked guanine O⁶ is undesirably alkylated, adding a cationic charge that changes hybridisation affinity and activates innate-immune sensors in vivo. In the sugar manifold, a free 2'-OH in RNA monomers cyclises onto the adjacent phosphate, making a cyclic triester that hydrolyses to strand scission during final deprotection. These side reactions are not statistical noise—they create specific, identifiable sequence truncations and point mutations that co-purify with the full-length oligonucleotide, requiring expensive re-runs of anion-exchange polishing or, even worse, repeating toxicology lots when the impurity profile drifts outside validated limits.

Each side reaction wastes an activated monomer and fuses growing chains into dead-end by-products, reducing the effective coupling efficiency from high-nineties to mid-eighties. Solid-phase synthesis being a multiplicative process, this seemingly small per-cycle loss multiplies into a factor of two reduction in the crude yield after sixty couplings. The impurity profile also broadens: branched chains bear extra positive charges that anchor them more strongly to the anion-exchange resin, slowing gradient times and solvent consumption. Developers that increase monomer excess to make up for the loss in yield and add an entirely new purification challenge with reagent-related impurities (siliconates from silyl decomposition, acrylonitrile from cyanoethyl degradation) that remain invisible at small scale yet overwhelm the column at kilomole scale.

Insufficient protection results in increased workload for the deprotection cocktail. Dilute aqueous ammonia that selectively removes benzoyl and acetyl groups must be supplemented with fluoride or more heating time if unexpected silyl or acetal adducts are encountered. Such more rigorous conditions promote depurination, which liberates the abasic site at unprotected adenosines that fragment under neutral pH. The global deprotection step becomes a competition between intended liberation and backbone cleavage, which can't be balanced once the oligonucleotide is still attached to the resin. The resulting product often has a greater proportion of shortmers, abasic strands and base-modified fragments that fail specification, leading to expensive re-synthesis and clinical delays.

We provide a comprehensive portfolio of protected nucleoside monomers designed to enable precise, efficient, and reproducible oligonucleotide synthesis. By combining optimized protection strategies with high-quality manufacturing and technical expertise, we help customers achieve high coupling efficiency, controlled reactivity, and consistent performance across RNA and DNA synthesis workflows.

Our portfolio includes a full range of protected nucleoside building blocks covering all canonical bases required for RNA and DNA oligonucleotide synthesis. These materials incorporate carefully selected base- and sugar-protecting groups that are compatible with standard solid-phase synthesis and phosphoramidite chemistry. All protected nucleoside monomers are manufactured to stringent specifications, ensuring high chemical purity, well-defined impurity profiles, and low moisture content. This level of quality is essential for maintaining sequence fidelity and minimizing side reactions during multi-step oligonucleotide assembly.

Effective protection strategies are critical for successful oligonucleotide synthesis. Our protected nucleoside monomers are designed using optimized, orthogonal protecting group systems that enable selective activation and deprotection throughout the synthesis cycle. These strategies support high coupling efficiency, clean deprotection, and minimal base damage, helping to reduce truncated sequences and simplify downstream purification. Our protection designs are compatible with both RNA and DNA synthesis, including workflows involving modified nucleosides and advanced chemistries.

For programs with specialized requirements, we offer custom protection and process development services. Our technical team works closely with customers to design tailored protecting group strategies, optimize synthetic routes, and control impurity formation. By addressing protection challenges early in development, we help ensure that custom protected nucleoside monomers are robust, scalable, and suitable for long-term manufacturing. This collaborative approach reduces technical risk and supports smooth progression from discovery to clinical production.

We support oligonucleotide programs at all stages with flexible and scalable supply options for protected nucleoside monomers. From small-scale research materials to larger-volume GMP-ready supply, our products are supported by clear specifications, traceability, and appropriate documentation. This end-to-end supply capability enables consistent raw material sourcing as programs advance, helping customers maintain quality continuity and regulatory readiness throughout development.

If you are looking for high-quality protected nucleoside monomers supported by deep technical expertise, our team is ready to assist. Contact us today to request technical information, samples, or quotations, or to discuss custom protection strategies and scalable supply solutions for your oligonucleotide synthesis program.

References

They contain multiple reactive sites that must be controlled during synthesis.

Side reactions, low yields, and incorrect sequences occur.

Yes, they are selectively removed during deprotection steps.

Proper protection significantly improves coupling yields.

Yes, they are essential for solid-phase synthesis.