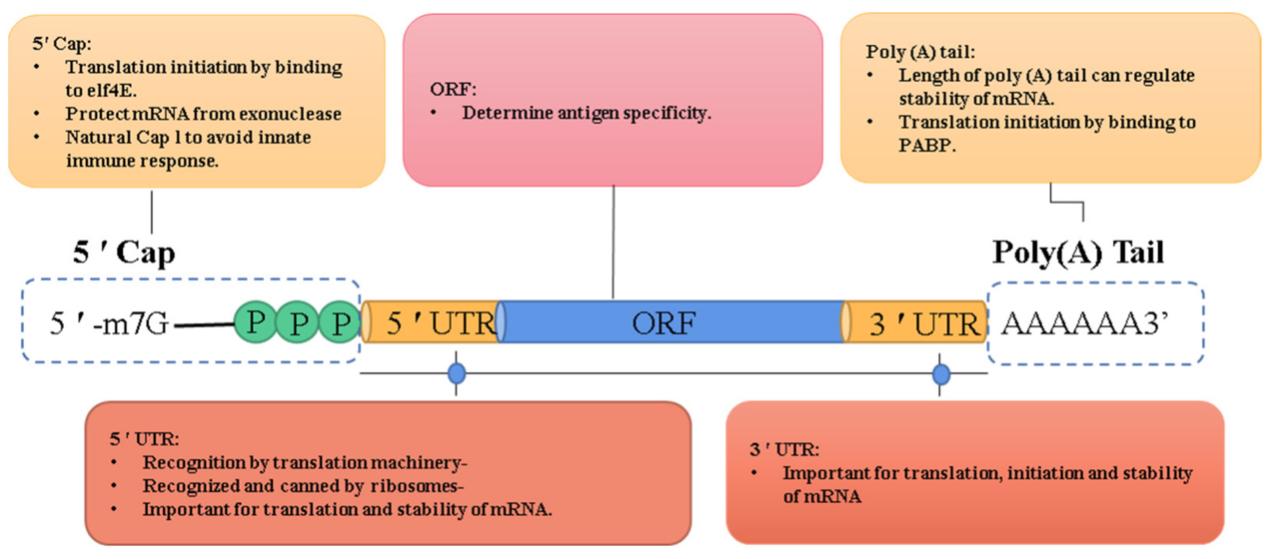

The advantage of cap analogs is that they restore the 5'-terminal structure of naturally occurring mRNA which, as a result of evolutionary forces, is one which is resistant to degradation and is optimized for translation. In other words, the mRNA cap creates a series of defense mechanisms against endogenous exonucleases and nucleases and nucleic acid sensors. The most obvious of these is the fact that a 5'-5' triphosphate linkage between the N7-methylguanosine and the first nucleotide in the mRNA prevents 5'-to-3' exonuclease activity, as the structure of the cap blocks the active site. The structure is also bound by specific proteins which form a protective cap-binding protein complex around the 5' end, which sterically inhibits phosphodiesterases and decapping enzymes.

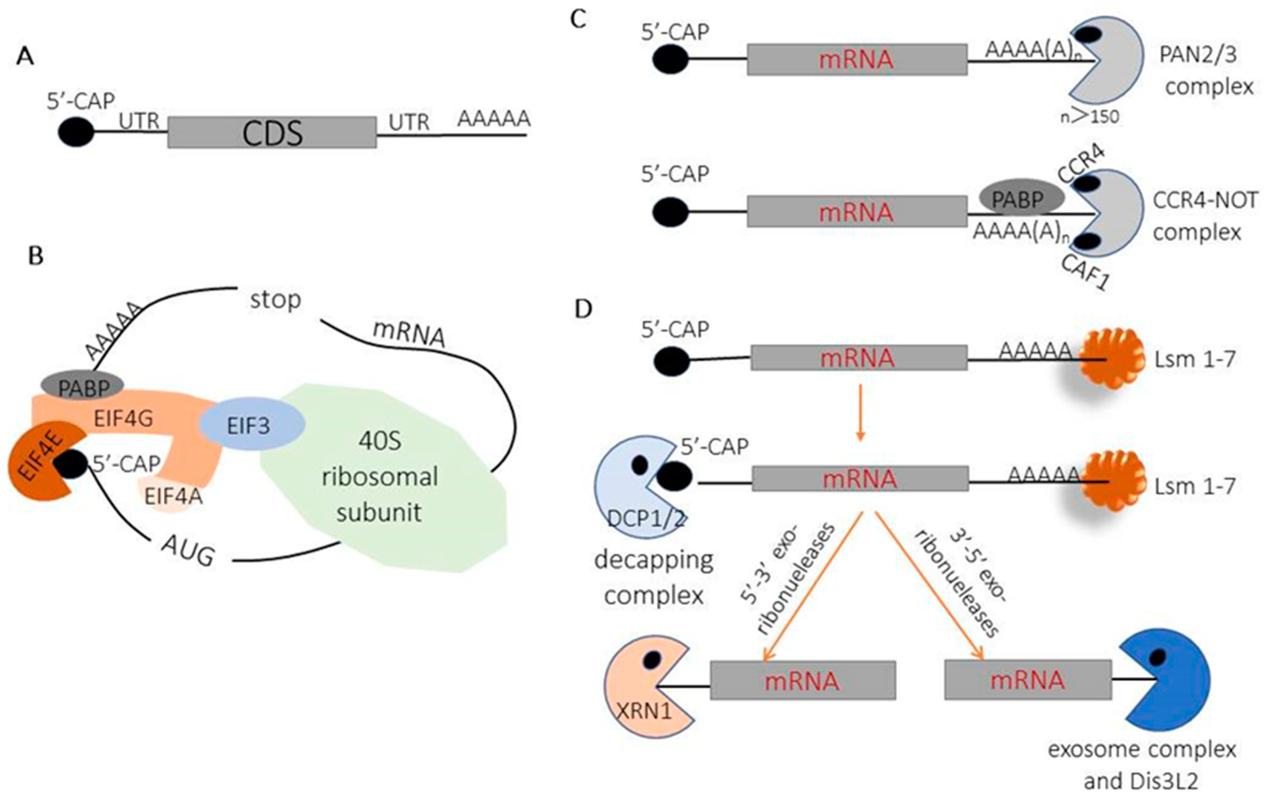

The degradation of mRNA in eukaryotes is mediated by two constitutive pathways that use a common rate-limiting step of 5' cap removal. The 5' cap is a critical gatekeeper determining whether an RNA is maintained for translation or destined for degradation. In the major pathway, the RNA is deadenylated, usually by the CCR4-NOT or PAN2-PAN3 complexes. Deadenylation destabilises the transcript, which is then decapped by the DCP2-DCP1 or NUDT16 decapping enzymes. Once decapped, the RNA body is sensitive to 5'-to-3' exonucleases such as XRN1, which digest the transcript to nucleotides. A minor decapping-independent pathway instead uses the 3'-to-5' exosome to degrade the transcript. This pathway is less efficient, as the 3'-to-5' exonucleolytic digestion of the entire RNA molecule is slower than 5'-to-3' digestion. In most conditions, this alternative decay pathway appears to be largely activated after the cap is lost. The 5' cap itself, which is required for translation, protects the transcript against both 5'-to-3' and 3'-to-5' decay through physical obstruction of the 5' access point, as well as through sterical exclusion of the decapping enzymes by cap-binding proteins. Under certain stress conditions such as amino acid starvation or interferon stimulation, this balance can be tipped by the inhibition of decapping by small molecules like adenosine 3',5'-bisphosphate, which maintains the transcripts in a capped state for stress-responsive translation.

Table 1 Comparative Features of mRNA Degradation Pathways.

| Pathway Component | Mechanism | Substrate Requirement | Cellular Location | Regulation |

| 5'–3' Exonuclease | Processive degradation after decapping | 5' monophosphate RNA | Cytoplasmic P-bodies | Deadenylation-dependent |

| 3'–5' Exosome | Multi-subunit exonucleolytic digestion | Deadenylated RNA | Nucleus and cytoplasm | Coordinated with deadenylation |

| Decapping Complex | Hydrolysis of 5' cap structure | Deadenylated mRNA with bound Lsm1–7 | P-bodies | Activator proteins enhance activity |

| Endonuclease | Internal cleavage bypasses deadenylation | Specific sequence/structure motifs | Cytoplasm | miRNA/siRNA-guided or regulated |

Schematics of cellular mRNA decay pathways.1,5

Schematics of cellular mRNA decay pathways.1,5

The 5'-to-3' exonuclease pathway is the most direct route of degradation for naked mRNA. Enzymes such as XRN1 are constitutively expressed in the cytoplasm and primed to attack any transcript without a cap. XRN1 is a processive exoribonuclease with affinity for free 5'-hydroxyl or monophosphate termini and it will digest the RNA chain in a 3' direction, liberating nucleoside monophosphates and completing turnover of uncapped transcripts within minutes. The 5' cap prevents this activity by creating a 5'-5' triphosphate bridge which cannot fit in the XRN1 active site, and the unusual geometry of this linkage sterically blocks initial binding and processive degradation. This effect is compounded in Cap 1 and Cap 2 by 2'-O-methylation that further occludes the 5' terminus and decreases the substrate's susceptibility to phosphodiesterases that may be present in high concentrations in inflammatory micro-environments. In addition to XRN1, the nuclear exonuclease Rat1/XRN2 is responsible for 5'-to-3' decay of transcripts retained in the nucleus. This decay pathway has particular relevance for therapeutic mRNA that might accumulate in nuclear speckles after delivery. The cap also serves to prevent degradation by serum RNases that are abundant in interstitial fluid and which would otherwise degrade unprotected RNA before it is taken up by cells. Some viruses have evolved complex cap-snatching mechanisms to overcome this protection, but for synthetic mRNA the cap is the only barrier to rapid exonucleolytic degradation.

The main decapping enzymes in the cell hydrolyze the 5' cap to generate the naked 5' end, which is immediately accessible to the 5'-3' exonuclease XRN1 and related exonucleases. DCP2, the primary decapping enzyme, forms a complex with DCP1. DCP2 contains a Nudix hydrolase domain that is responsible for the hydrolysis of the α-β phosphoanhydride bond in the cap structure to generate m⁷GDP and a 5'-monophosphate. XRN1 directly binds to the monophosphate, triggering mRNA degradation. DCP1 acts as a co-factor to stabilize DCP2 and facilitate the binding of accessory proteins that determine transcript fate. Dhh1 and Rap55 are two proteins that bind to DCP1 and target poorly translated transcripts for decay, in a way that appears to sense translational status. A second decapping enzyme, NUDT16, also participates in decapping in certain cell types. NUDT16 has distinct substrate specificities and plays an important role in removing non-canonical caps. The interferon-inducible enzyme DXO is both a pyrophosphatase and a 5'-3' exonuclease. DXO rapidly degrades Cap 0 and Cap 1 transcripts, but is sterically inhibited by the second 2'-O-methyl group in Cap 2. Some cap analogs, such as those with a phosphorothioate or methylenebisphosphonate bridge, are resistant to decapping. Such capped transcripts show an increase in half-life from hours to days. The 5' cap is also a target for regulation by upstream deadenylation events, as the poly(A) tail recruits the LSM1-7 complex, which stimulates DCP2 activity.

Cap analogs are a common way to protect chemically synthesized mRNA. The caps of these analogs are chemically similar to the naturally occurring cap, but have additional protective mechanisms. Each cap analog is composed of a 7-methylguanosine (m7G) connected to the mRNA with modified triphosphate linkages. The modifications provide steric and electrostatic protection from cleavage. First, structural modifications prevent 5'-to-3' exonucleases from cleaving the mRNA by preventing the enzyme from recognizing the terminal phosphate. The secondary structure and closed-loop structures further protect the 5' and 3' ends of the transcript. The cap analogs also recruit cellular proteins like eukaryotic initiation factor 4E and cap-binding protein complexes to protect the RNA from degradation by forming ribonucleoprotein complexes that sterically hinder enzymes from accessing the RNA. Phosphorothioate substitutions and elongated phosphate linkages between the guanosine and mRNA also make the linkages resistant to decapping pyrophosphatases. The additional protection of cap analogs is crucial to allow the mRNA to have enough stability to translate a functional protein before degradation.

The five key domains of IVT mRNA and their function.2,5

The five key domains of IVT mRNA and their function.2,5

The design of cap analogs inhibits 5' exonuclease binding, because of their structure they do not allow for exonuclease docking. The key protective feature is the 5',5'-triphosphate bridge connecting the 7-methylguanosine and the first transcribed nucleotide in an inverted manner. The 5',5' triphosphate bridge is a structure that cannot be accommodated in the active sites of Xrn1 or other 5'-to-3' exonucleases because these enzymes require an unobstructed monophosphate or hydroxyl group to function. In addition, the N7-methylated guanosine base is bulky and positively charged, which also interferes with enzyme docking. The triphosphate is also negatively charged, which contributes to the electrostatic repulsion of enzymes. More recent cap analogs incorporate a phosphorothioate bridge, in which the non-bridging oxygen is replaced with a sulfur atom. This phosphorothioate link cannot be cleaved by a phosphodiesterase. The orientation of the analogs is determined by an anti-reverse feature, which prevents the formation of other alternative cap structures that might expose the 5' terminus. Methylene or imidophosphate substitutions between phosphate groups also make it more difficult for pyrophosphatases to bind. All of these protective features serve to prevent the progressive degradation of the transcript by the exonuclease and increase the half-life of the transcript from minutes to hours. Translation initiation factor binding provides additional protection, with eIF4E binding effectively occluding the 5' end of the transcript from Xrn1 docking.

Cap analogs also stabilize the global structure of mRNAs. The cap structure induces base stacking at the end of the transcript that can also stabilize the local secondary structure, decreasing conformational freedom and the resulting endonuclease sensitivity. The ability of the cap-binding protein to recruit a complex of eIF4E and eIF4G that bind the poly(A)-binding protein to form the closed-loop structure of mRNA, protects both the 5' and 3' end of the transcript from exonuclease activity. This circularization of the transcript increases the local concentration of the mRNA and decreases the conformational entropy leading to more stable, condensed structures. Cap analogs can also alter the translation initiation rate of the transcript. As ribosomes are actively translating the transcript, they protect the mRNA from endonucleases by occluding the mRNA from the nucleases as they pass along the coding sequence. The cap also inhibits activation of innate immune sensors that detect the uncapped transcript leading to recruitment of complexes that result in mRNA degradation. Modifications to the structure of the cap analog, including 2'-O-methylation and increased bridge length of phosphate groups, have also been shown to increase binding affinity to proteins that stabilize the mRNA-protein complex. These factors have a major effect on stability of mRNAs during storage, delivery and intracellular trafficking.

Cap analogs are translated by means of a protein specific to the 7-methylguanosine modification and capable of forming part of a stabilizing ribonucleoprotein. The predominant cap-binding protein is the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), part of the eIF4F initiation complex which directly binds to the mRNA end and occludes potential binding sites of decay enzymes and activators, thus initiating translation. Additionally, eIF4E recruitment of eIF4G is capable of binding to poly(A)-binding protein and creating the closed loop complex. This form of stabilization is shared by both ends of the transcript. In the nucleus, CBP80 and CBP20 cap-binding proteins bind the transcripts and protect them from early degradation. They are involved in both splicing and polyadenylation. Their interaction with the cap structure is stronger when Cap-1, the optimal structure, is present, therefore conferring a longer half-life. In contrast, decapping enzymes (Dcp2 and Nudt16) responsible for 5'-3' mRNA degradation do not recognize cap analogs with phosphorothioate modifications. The substituting sulfur is capable of sterically hindering Dcp2 and Nudt16, without affecting binding to eIF4E. Cap analogs also block recognition of the modified RNA by pattern recognition receptors like RIG-I and MDA5. The protein binding capabilities of the cap analogs make it capable of occluding access by other molecules to the 5' end. For example, the assembly of the translation machinery is able to outcompete the mRNA decay factors.

Table 2 Protective Mechanism.

| Protective Mechanism | Molecular Basis | Functional Outcome |

| Exonuclease Blocking | Inverted triphosphate bridge, steric hindrance, phosphorothioate modifications | Prevents Xrn1 binding and processive degradation |

| Structural Stabilization | Cap-mediated closed-loop formation, base stacking, reduced conformational flexibility | Enhanced global mRNA stability and ribosome shielding |

| Protein Interactions | eIF4E recruitment, decapping enzyme resistance, immune evasion | Formation of protective ribonucleoprotein complexes |

Each Cap analog has a different stability. This property is important for determining how long synthetic mRNA is functional and can determine the effectiveness of the therapeutic. The differences in stability between Cap analogs is hierarchical. Cap 0, which is a Cap analog without any ribose methylation, is the least stable. It is susceptible to decapping but is somewhat resistant to exonuclease activity. Cap 1, which has 2'-O-methylation on the penultimate ribose, is more stable than Cap 0. It is more likely to bind eIF4E and less likely to activate pattern recognition receptors that recognize incomplete capping. The anti-reverse Cap analog has increased stability because it removes cap orientation heterogeneity and virtually 100% of caps are in the correct orientation. Modifications to the triphosphate bridge, such as phosphorothioate or methylene linkages, also increase stability, as these modifications are more resistant to Dcp2, but they do not affect eIF4E binding.

Cap 0 and cap 1 are very differently stable in mammalian cells. Cap 0, which is the most minimal cap structure possible in terms of function, is N7-methylguanosine linked to the first transcribed nucleotide by a 5'–5' triphosphate bridge. This structure, while protected against 5'–3' exonucleases by the cap, is not protected against interferon-inducible factors that recognize unmethylated 2'-hydroxyls of the first transcribed nucleotide as foreign. This recognition by innate immune sensors makes cap 0 less functionally stable, as transcripts with cap 0 structures activate a variety of pathways that speed the degradation of these transcripts and prevent their translation. Cap 1, with an extra 2'-O-methyl modification on the first transcribed nucleotide that matches the chemical signature of endogenous mammalian mRNA, has more similarity to endogenous mRNA and is less likely to activate pattern recognition receptors, resulting in longer transcript half-life. The 2'-O-methyl group also increases the binding affinity for eukaryotic initiation factor 4E, stabilizing eIF4F complex formation and helping protect the mRNA from decapping and exonucleases. The difference in stability between cap 1 and cap 0 is likely most significant in vivo, due to the presence of the mammalian innate immune system's RNA sensors.

ARCA provides stability benefits over the unmodified dinucleotide cap due to the solution of the orientation issue, but remains a poor protective cap overall because of the base Cap 0 structure. The reverse incorporation protection provided by the 3'-O-methyl modification to the guanosine ribose forces all of the structures to be translationally active, indirectly stabilizing the transcript by binding the eIF4E translation initiation factor and protecting the end from nucleases. This means, however, that the transcript is still sensitive to translational arrest by IFIT1 and decapping by DXO due to the unmethylated ribose on the first nucleotide, as both of these immune sensors are common in myeloid cells. This also means that the protection gained from forward orientation is a double-edged sword: forward ARCA caps are as stable as Cap 0 (minus the small amount of non-functional reverse caps), but any small amount of non-functional reverse caps act as inhibitors and will compete for eIF4E to lower the functional translation rate of the mRNA. The result is a modest increase in stability of the overall capped species but not to the basic level of protection from immune degradation pathways, making it a good intermediate option for preclinical studies and uses where intermediate expression times are acceptable but not robust enough for chronic treatments.

Capping efficiency critically impacts mRNA stability, as uncapped RNA represents a minority population with a rapid turnover, leading to a decreased net concentration of stable RNA and heterogeneity in the RNA pool that can affect dosing precision. A high capping efficiency (dependent on factors such as optimal cap-to-NTP ratios, template architecture, and enzyme choice) is desirable to ensure a uniform RNA population where each molecule is protected from immediate degradation and is translationally active. Conversely, low efficiency results in a mixed population where uncapped transcripts are quickly degraded by XRN1, releasing nucleotides for salvage pathways and, more critically, producing an array of degradation products that may inadvertently stimulate RIG-I and MDA5, causing off-target IFN induction. The impact on stability is not linear: if the efficiency drops below 80%, the pharmacokinetic profile of the mRNA becomes unpredictable, with protein expression no longer reflecting the dose due to inconsistent degradation rates of the uncapped fraction. As a result, regulatory authorities require capping efficiency as a quality metric, typically assessed by mass spectrometry or enzymatic cleavage methods to confirm that the uncapped fraction is below a specified limit, ensuring that the therapeutic mRNA acts as a uniform compound with a predictable half-life and activity. For long-term expression applications, such as protein-replacement therapies, the efficiency needs to be greater than 95% to ensure the mRNA reservoir is stable enough to support ongoing protein production between doses.

Experimental support for cap-dependent stability has been demonstrated by showing a marked difference in half-life and protein expression from capped and non-capped transcripts. For example, when in vitro transcripts are synthesized in the presence of a cap analog, they are found to be stable to cell lysate, while the same transcripts without a cap are degraded within a few hours. Transient expression of capped and non-capped mRNA in cells has shown that the capped version is more stable over time, with a consistent expression of a reporter gene, such as a luciferase reporter. Protection from degradation has also been confirmed by incubation with exogenous decapping enzymes, showing that a modified cap is protected from enzymatic removal, and is still able to bind translation factors. Measurement of mRNA half-life by metabolic labeling has also confirmed that capped mRNA is stable for a much longer time than non-capped mRNA. These findings support the 5' cap as being the primary determinant of mRNA stability.

The integrity of mRNA is usually tested by incubation of capped transcripts under defined conditions which mimic a cellular context, and the kinetics of degradation is determined as a function of time. Degradation is typically monitored by gel electrophoresis or HPLC, and has shown that mRNAs capped with modern analogs retain integrity after incubation for extended periods in cell lysates or media containing serum. Enzymatic challenge experiments with recombinant decapping enzymes have shown that the cap analogs with phosphorothioate linkages or extended phosphate backbone are resistant to hydrolysis, while the standard cap is quickly removed. A variety of different caps were also compared, and the results show that analogs designed with better stability are retained even under more stringent conditions which drive nuclease activity. The stability of different caps was also measured in the presence of competing nucleotides and other conditions relevant to therapeutics like different pH levels, and it was shown that modified phosphate backbone are better protected.

Expression in cells is an appropriate assay to verify the functional consequence of cap analog protection. This is achieved by introducing the capped mRNA to cells and quantifying the protein production over time. When using luciferase or fluorescent protein reporter assays, mRNAs with optimized cap analogs typically have higher protein expression levels than standard capped mRNA in vitro, indicating increased stability as well as higher translation efficiency. Time course experiments typically show that translation of protected mRNA can be maintained over several days with delayed time to maximum protein levels and often prolonged expression. Immunostaining of transfected cells is able to directly demonstrate that the capped mRNA is protected from degradation, often remaining in the cytoplasm and continuing to make protein while uncapped mRNA transcripts are rapidly lost from the cell. Immunogenicity studies using modified caps show that modified mRNA can be administered repeatedly without a reduction in expression efficiency. Comparative experiments with various cell lines, including immortalized and primary cells, demonstrate that the enhanced stability and other properties of optimized cap analogs are maintained across a wide range of cell types.

Protecting mRNA from degradation begins with effective 5' capping, and the structure and quality of the cap analog play a decisive role in maintaining mRNA integrity. Our high-stability cap analogs are specifically designed to support robust protection of the 5' end during in vitro transcription (IVT) and downstream handling, helping preserve mRNA structure and functionality throughout the workflow. These products are optimized to minimize degradation pathways while maintaining compatibility with standard IVT systems.

Our cap analogs are engineered to form a stable and correctly oriented 5' cap structure that effectively shields mRNA from 5'–3' exonuclease-mediated degradation. By promoting efficient cap incorporation and strong interaction with cap-binding proteins, these reagents help maintain mRNA integrity during transcription, purification, and storage. This design approach supports longer mRNA half-life and reduces variability caused by partial or unstable capping.

The protective function of a cap analog must be demonstrated under real IVT conditions. Our high-stability cap analogs have been validated in commonly used IVT mRNA systems, showing consistent capping efficiency and reproducible protection against degradation. Rigorous quality control and analytical testing ensure predictable performance across batches, supporting reliable mRNA synthesis and stable downstream expression outcomes.

Maintaining mRNA stability is essential for achieving consistent expression and reproducible results, and selecting the right cap analog is a foundational step in controlling degradation. Whether you are optimizing IVT conditions or addressing stability-related challenges, our high-stability cap analogs are designed to support robust mRNA integrity—contact us today to discuss your requirements and request technical information or a quotation.

References

mRNA degradation often begins at the 5' end through exonuclease activity.

Cap analogs form a protective structure that blocks exonucleases from accessing the 5' end.

Yes, more stable and correctly oriented caps improve resistance to degradation.

Yes, improperly capped mRNA is more susceptible to degradation during handling and storage.

Cap analog performance is commonly validated under IVT conditions to assess stability.