Chemical and enzymatic capping are the two most commonly used approaches for the addition of 5' cap structures to IVT mRNA. Both methods have their own benefits and drawbacks that impact their scalability, product quality, and downstream performance. Chemical capping typically involves the use of synthetic cap analogs which are incorporated during the transcription reaction (co-transcriptional), thus leading to a simplified one-pot procedure, with reduced steps and manufacturing time. This approach provides flexibility in cap structure design, including the use of non-natural modifications. On the other hand, enzymatic capping more closely mimics the natural cellular capping process, as recombinant enzymes are used to modify the 5' end of mRNA after transcription has occurred (post-transcriptional). This approach can result in near-quantitative capping efficiency and the ability to create a true Cap 0, Cap 1, or Cap 2 structure with high fidelity. This comes at the expense of increased process complexity, manufacturing time, and higher cost due to the need for additional purification steps and enzyme.

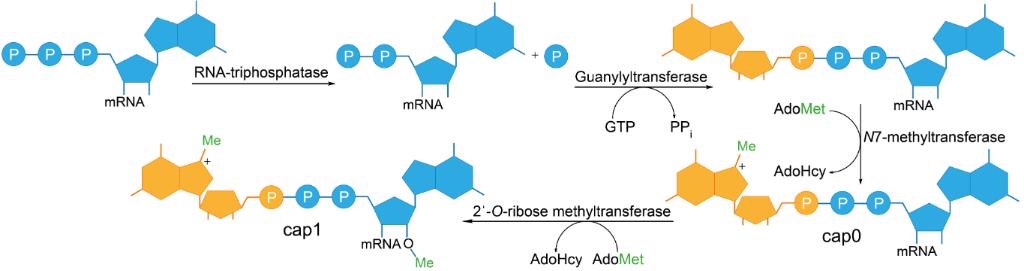

Schematic representation of enzymatic 5'-cap formation in eukaryotic mRNA1,2

Schematic representation of enzymatic 5'-cap formation in eukaryotic mRNA1,2

Chemical and enzymatic capping reactions are the two mRNA capping strategies. The main difference between the two methods is based on when, how, and what type of cap structure is added to mRNA. In chemical capping, mRNA is transcribed in the presence of synthetic cap analogs, so capped and uncapped mRNA coexist in the same reaction vessel during in vitro transcription. This is also called co-transcriptional capping. Chemical capping takes advantage of the capability of some RNA polymerases to initiate transcription using cap dinucleotides as substrates instead of guanosine triphosphate (GTP). Optimization of the ratio between the cap analog and GTP usually improves the efficiency of cap incorporation during chemical capping. On the other hand, enzymatic capping is also known as post-transcriptional capping, and consists of modifying pre-synthesized mRNA with recombinant enzymes, which is more similar to the in-cell capping process. Enzymatic capping requires a multi-step reaction involving enzymes with RNA triphosphatase, guanylyltransferase, and methyltransferase activities. This reaction is called enzymatic cascade and generates the natural cap structure (Cap0 and Cap1). There are benefits and drawbacks to both strategies, and the choice of capping method is based on the desired efficiency, the feasibility, the acceptable complexity of the manufacturing process, cost, and regulatory requirements. Both strategies have been improved recently; for example, novel cap analogs have been developed to improve chemical capping, and enzyme engineering has been performed to improve enzymatic capping robustness and decrease the cost.

Chemical capping, also known as co-transcriptional capping, is a simplified method of mRNA 5' modification. Synthetic cap analogs are added to in vitro transcription reactions, as bacteriophage RNA polymerases have been found to use cap dinucleotides as a substrate in place of guanosine triphosphate. Cap analogs are directly added to in vitro transcription reactions where they compete with GTP to be incorporated at the 5' terminus of the transcript. Cap analogs from the first generation such as m7GpppG had an orientation problem. The caps could be added in either a "functional" orientation or a "reverse" orientation, where the 7-methylguanosine is at the 3' end of the 5' cap structure. This leads to a very large decrease in the amount of translation competent transcripts that are generated. The development of anti-reverse cap analogs (ARCAs) was enabled by the specific chemical modification of cap analogs in a way that would allow only 5' to 3' incorporation of the cap. This ensured that only the 7-methylguanosine moiety would be at the 5' terminus of the cap in a "functional" orientation. Trinucleotide and tetranucleotide cap analogs are also available that allow for the direct transcription of Cap 1 or Cap 2 structures, without the need for enzymatic capping. This method of capping is very simple, and is generally more economical since transcription and capping occur in a single reaction mixture, and fewer steps are required for mRNA production. Drawbacks of the method include a lower overall capping efficiency when compared to enzymatic methods, and the large molar excess of cap to GTP required, which makes the raw materials for the reaction more expensive.

Enzymatic capping, as the name suggests, involves mimicking of cellular 5' cap structure addition reactions. In this approach, in-vitro-transcribed RNA is purified to remove the unincorporated nucleotides and other transcription reaction components. The purified RNA is incubated with recombinant RNA triphosphatase, guanylyltransferase and methyltransferases which sequentially process the 5' end of RNA. The γ-phosphate is removed and guanosine monophosphate is added by 5'–5' triphosphate linkage to RNA. The enzymes further methylate the N7 atom of the guanosine moiety to generate Cap 0. Methylation of the 2'-O position of first nucleotide can be done by a 2'-O-methyltransferase to give Cap 1. This method has the highest fidelity and near quantitative capping efficiency (efficiency). Due to the additional purification step, it is time and cost intensive. Enzymatic capping is the method of choice for therapeutic applications as the end product uniformity and biological authenticity is more suitable for these applications. As with all post transcriptional capping methods, enzymatic capping is suitable for all RNA sequences and lengths of interest.

Table 1 Comparison of Chemical Capping and Enzymatic Capping

| Aspect | Chemical Capping | Enzymatic Capping |

| Process Integration | Single-step, co-transcriptional | Multi-step, post-transcriptional |

| Capping Efficiency | Moderate to high with optimization | Typically high, approaching quantitative |

| Cap Structure | Depends on analog design | Natural, authentic cap structures |

| Manufacturing Complexity | Simplified, fewer unit operations | Complex, requires multiple steps |

| Cost Considerations | Lower processing costs, higher raw material costs | Higher processing costs, enzyme expenses |

| Scalability | Straightforward scale-up | Enzyme supply chain considerations |

| Quality Control | Mixed populations, purification needed | High purity with proper optimization |

Chemical capping refers to a one-pot method for the addition of 5' cap structures during the process of in-vitro transcription. It is a simple method that is attractive for many uses that value rapid synthesis and procedural simplicity. Chemical capping is often done by simply adding the desired synthetic cap analog directly to the transcription reaction. The method is therefore fast and obviates any need for post-synthetic enzymatic capping. However, a major drawback is that the capped and uncapped RNA species compete with each other for initiation. Additionally, the original m7GpppG cap analog is directionally heterogeneous so that up to 50% of capped transcripts have the cap incorporated in the reverse direction (termed "mirror capping"), leaving them non-functional with respect to translation. Although later analogs, such as ARCA and trinucleotide caps, are able to avoid this problem, chemical capping in its original form is unable to create more complex structures (such as Cap 1 or Cap 2) without some additional enzymatic manipulation. For these reasons, the method is generally seen to be well suited for research and early development work but is limited in therapeutic applications.

Chemical capping can greatly simplify the overall mRNA production workflow, since the cap structure can be incorporated co-transcriptionally, without the need for post-transcriptional enzymatic processing or intermediate purification steps. In general, the cap analog is directly added to the in-vitro transcription reaction, and the RNA polymerase then uses the analog as a primer to initiate transcription. This integration of the capping step can decrease the total number of unit operations, as well as sample handling and production time. The decreased complexity also reduces the likelihood of product loss or degradation during intermediate purification steps, which can be important when working with small amounts of material or for rapid prototyping. Chemical capping is also well suited to automation on liquid-handling platforms, which can further simplify and increase the throughput of the workflow for screening or other high-throughput research applications. Workflow simplification must be weighed against the limitations in capping efficiency and structural fidelity described above, particularly for simple analogs that will produce a mixed population of correctly and incorrectly capped RNA. Analog formats like ARCA or trinucleotide caps offer an increase in performance while still maintaining the advantages in workflow simplicity.

Efficiency is a general limitation of all chemical capping methods. As the initiation reaction is a competition between the cap analog and GTP for incorporation at the 5' end of the new transcript, it is inherently sub-optimal. As a result, the reaction often produces a heterogeneous mixture of capped and uncapped mRNA, with only a portion of the capped molecules being translationally competent. The resulting fraction of functional transcripts produced varies with the cap/GTP ratio and the analog itself. The efficiency of standard dinucleotide analogs such as m7GpppG is typically moderate, but this approach also suffers from an orientation bias, which can reduce the fraction of functional capped RNA molecules still further. ARCAs and trinucleotide caps can increase efficiency as well as orientation-specificity by blocking reverse incorporation, and by increasing binding affinity of the cap analog for the RNA polymerase. Even with the most efficient analogs, however, chemical capping is generally not as near-quantitative as enzymatic capping methods. Uncapped transcripts may have undesirable biological effects by inducing innate immune responses, and can lead to reduced expression if significant in sensitive applications such as in vivo delivery or therapeutic development. Manufacturers may attempt to address this issue by running the reaction at lower GTP concentration, or with increased input of cap analog, but this can result in decreased overall RNA yield.

Chemical capping has potential advantages in terms of cost and scalability, and may be especially attractive for large-scale or high-throughput applications where factors like operational simplicity or reagent cost are particularly important. It obviates the need for enzymes and additional purification steps, saving on both materials and labor, and bulk quantities of cap analogs, though they are chemically more elaborate, can be readily synthesized via scalable organic chemistry. The capped products are also directly ready-to-use and can be transcribed without special equipment or processing conditions under otherwise standard conditions. This allows chemical capping to be well-suited to automation and parallelization, facilitating large-scale production of capped mRNA with minimal equipment investment. The simplified process also reduces opportunities for batch-to-batch variability and product loss, further improving cost-effectiveness. Of course, this cost advantage needs to be balanced with the restrictions on capping efficiency and product quality that result from using basic analogs that do not yield as high a proportion of capped, functional transcripts. The more stringent requirements for high-quality, uniformly capped mRNA for therapeutic applications may necessitate the extra investment in enzymatic capping or in more elaborate, and thus more expensive, analogs. On the other hand, for research, preclinical development, or clinical use in settings where moderate levels of capping efficiency are acceptable, chemical capping provides a cheap and scalable alternative. Improvements in analog design and process development are further increasing the cost-effectiveness of chemical capping for clinical applications.

Table 2 Summary of Chemical Capping Advantages and Limitations

| Aspect | Chemical Capping Advantages | Chemical Capping Limitations |

| Workflow | Single-step, integrated process | Requires optimization of cap:GTP ratio |

| Efficiency | Good with anti-reverse analogs | Mixed populations requiring purification |

| Cost Structure | Lower processing costs | Premium raw material pricing |

| Scalability | Straightforward scale-up | Raw material supply chain dependency |

| Manufacturing | Reduced facility footprint | High reagent consumption rates |

The most biomimetic strategy is to recreate the cascade of reactions in cells in vitro, removing the triphosphate, installing the GMP, and then methylating. This can be carried out with recombinant enzymes (or virus-encoded enzymes), but leads to extended workflows, increased cost, and narrower enzyme supply chains. This is due to the fact that each reaction step is mediated by a separate recombinant enzyme. In theory, this strategy can lead to almost quantitative conversion to either Cap 0 or Cap 1 with very low levels of mis-oriented caps. The high level of purity of the capped product is generally considered to be the dominant advantage over competing methodologies and can often justify the additional burden and cost when making clinical grade material. However, with recent development of viral enzymes that are stable to high temperatures, the enzymatic capping reaction can be run in a one-pot, transcription coupled format at higher temperatures, which helps reduce the timeline burden. In general, the sequential incubations, SAM-dependent methylations and additional purification steps required for enzymatic capping increase the cost-of-goods over chemical alternatives. In addition, the tight enzyme supply chain is becoming a potential risk factor for developers: only few companies manufacture GMP-grade triphosphatase, guanylyltransferase, and 2'-O-methyltransferase. As a consequence, any upstream disruption to these enzymes can have immediate impact on late-stage programs. For these reasons, enzymatic capping is generally used whenever regulatory focus, immune evasion, or Cap 1 authenticity are key features of the target product profile.

The enzymatic capping reaction is the most widely used method for the synthesis of Cap 1. This method is a two-step reaction that mimics the modification pattern found in authentic mammalian mRNA, namely, the 2'-O-methylation that can prevent recognition by innate immune system. In the first step, the Cap 0 structure is formed by the sequential addition of RNA triphosphatase, guanylyltransferase, and guanine-N7 methyltransferase. The 2'-O-methyltransferase then modifies the ribose sugar of the first transcribed nucleotide by methylating the 2'OH to form Cap 1. The methoxy group present at 2' position is a distinguishing feature of Cap 1 that is responsible for immune evasion. Reaction conditions can be optimized to shift the equilibrium towards Cap 1 formation by increasing the reaction temperature and enzyme ratios. This method provides high conversion of transcripts with authentic Cap 1 structure, with minimal degradation of the transcripts. The greater biological authenticity of enzymatically modified Cap 1, in terms of the modification pattern, results in improved resistance to innate immune sensing when compared to chemically modified Cap 1. The one-pot synthesis of Cap 0 and Cap 1 is also possible, with the aid of thermostable enzymes, where both reactions are allowed to proceed in the same reaction vessel.

The process complexity is the most significant bottleneck of enzymatic capping. Process complexity implies additional unit operations which prolong production timelines and subject the product to more quality control testing relative to the chemical method. The entire procedure consists of several enzymatic reactions, each of which requires specific reaction conditions, co-factors, and reaction optimization for the best performance. Reaction conditions for initial RNA synthesis, for example, must be compatible with preserving the 5' triphosphate for enzymatic capping. This can require altering or optimizing transcription reaction conditions and can necessitate the incorporation of modified nucleosides. Once the RNA is synthesized, purification must occur to remove impurities from the reaction mix that would otherwise inhibit the capping enzymes. Capping itself is also a multistep process, with a number of enzymes required in concert and at specific molar ratios. In addition to each enzyme requiring a specific buffer, co-factors (S-adenosylmethionine for example), and reaction optimization, temperature must be tightly controlled. While higher temperatures will improve enzyme kinetics, they may also risk RNA integrity or denature the enzyme. The reaction's multistep nature also creates more opportunities for loss of product, either from incomplete reactions, inefficient enzymes, or a purification step in between reactions. Quality control of the finished product is more complex, as each step of the reaction must be monitored and validated. Acceptance criteria must also be established for the intermediate product after capping. By its very nature, the reaction creates more impurities than a single chemical reaction.

Recombinant cap-forming enzymes are produced at relatively low volume and with long lead-times because expression hosts (mostly E. coli or insect cells) require dedicated fermentations suites and refolding/purification infrastructure to achieve multi-column purification to drug-worthy levels of purity and activity. Unlike the oligonucleotide-modifying enzymes such as restriction endonucleases, the cap-enzyme trifecta (triposphatase, guanylyltransferase, and 2'-O-methyltransferase) is available from just a few manufacturers; supply chain bottlenecks are inevitable if the world's annual demand is to be fulfilled on pandemic scale (e.g. mRNA vaccine production campaigns). Consequently, even the microgram-scale, research vials are sold at high prices and GMP (kilogram-scale) lots have a high share of the mRNA bill-of-materials (cost of goods sold). Cold-chain and stability limitations are non-transparent additional costs: e.g., the guanylyltransferase component is prone to lose activity with freeze–thaw cycles, and SAM (the universal methyl donor) quickly hydrolyses in aqueous buffers and must be prepared just-in-time, and stored under refrigerated conditions. Supply risk from currency changes or unexpected intellectual-property disputes around viral-enzyme sequences could severely limit availability overnight and force developers to qualify new second-source suppliers, a multi-month effort that would cause significant clinical delays. On the other hand, enzyme engineering (e.g., for thermo-stability or single-chain fusions) is slowly driving up volumetric productivity and reducing the stoichiometry required, but these next-generation enzymes are only now working through regulatory qualification. No truly commoditised, cell-free enzyme production platform exists yet, so supply and price volatility will remain a strategic risk of the enzymatic approach.

Table 3 Enzymatic Capping-Key Strengths and Limitations

| Parameter | Enzymatic Capping Advantages | Enzymatic Capping Limitations |

| Cap 1 Formation | Precise, natural methylation patterns | Requires multiple enzymatic steps |

| Process Complexity | High fidelity, authentic structures | Multi-step workflow, extended timelines |

| Enzyme Supply | Improving through engineering | Premium pricing, supply chain dependency |

| Product Quality | Natural cap structures, high efficiency | Complex quality control requirements |

| Manufacturing | GMP-compliant processes available | Higher processing costs, specialized expertise |

Direct comparison of chemical and enzymatic capping approaches highlights intrinsic differences in efficiency, product yield, process control, and manufacturing scalability, all of which have direct implications on the choice of platforms for mRNA production. Chemical capping allows co-transcription and cap modification to take place in a single reaction vessel, while enzymatic capping strategies have the advantage of higher biological fidelity in terms of the native cap structure. The decision-making process goes beyond the performance parameters and delves into the philosophy of manufacturing, with chemical methods being geared toward speed and simplicity, and enzymatic methods being driven by a quality and precision focus. Recent technological advancements have begun to close the performance gap between the two methods, with new cap analogs being developed to improve the efficiency of chemical capping, and enzyme engineering making enzymatic approaches more robust. The choice between the two ultimately depends on the specific application needs, with research applications tending to lean toward chemical methods for rapid development, and clinical manufacturing increasingly favoring enzymatic methods for improved product quality.

Efficiency and yields between enzymatic and chemical capping are different. Efficiency is generally higher for enzymatic capping, due to the ordered mechanism of a cascade of enzymes that are often derived from the corresponding cellular pathway. Enzymatic capping can approach 100% modification of input transcripts, resulting in a lower amount of uncapped, contaminating transcripts in the reaction product and less purification steps. Chemical capping was not as efficient as enzymatic capping, as a portion of the capped transcripts was still not capped. Advances in the chemical capping process, such as the use of anti-reverse cap analogs and a trinucleotide analog that results in a ready-made Cap 1 after ligation, have significantly improved the efficiency of chemical capping. However, capping reaction conditions, such as cap-to-GTP ratios, must be chosen so that the capping efficiency is high enough to prevent low-yield incorporation of GTP at the 5' ends of transcripts, but not so high as to waste capping reagents and further decrease overall transcription yield. In a competitive incorporation reaction, some transcripts will be initiated with GTP instead of cap analog. Enzymatic capping is generally more robust across a range of transcript sequences and lengths. Since the efficiency of chemical capping is determined by the kinetics of polymerase-mediated cap analog incorporation, template sequence and length can play a role in efficiency. This has been somewhat improved by more process intensive methods such as fed-batch and reaction condition optimization for both chemical and enzymatic capping methods.

Process control is another point of differentiation. Enzymatic capping offers more points of control, with each step in the process being individually defined, optimized, and monitored. Reaction parameters such as enzyme concentration, reaction time, and reaction conditions may be adjusted during the process to meet product specifications. The multi-step approach also allows for intermediate quality control to ensure the material meets specifications before proceeding to the next step in the process. Process controls can also extend to the methylation status of the cap with enzyme timing and ratio affecting whether Cap 0, Cap 1 or Cap 2 modifications are produced. Chemical capping, being co-transcriptional and occurring in a single reaction vessel, offers less intermediate control points for the incorporation of the cap into the RNA molecule. Kinetic control of the reaction, however, is more easily controlled with chemical capping by adjusting the concentration and ratio of cap analog to GTP, allowing for fine-tuning of the efficiency without interrupting the reaction. In addition, the single-pot nature of the reaction offers less opportunity for operator error and contamination from multiple steps and processing. Method control for both approaches still requires extensive analytical controls, with enzymatic approaches requiring monitoring of multiple enzyme activities and chemical methods requiring control over orientation purity and capping efficiency.

Industrial scalability A large-scale operation is one that can process materials in the kilogram-range. For chemical capping, the advantage is that it is very easy to scale up and can be performed in one-pot, meaning that the final reaction vessel just needs the addition of the raw materials to the in vitro transcription mixture already in the production reactor. The enzymatic capping pathway is slightly more involved, but has been used at kilogram-scale in the past. The capital investment and facility space required at industrial scale are lower for chemical capping, as are the operating complexities. Product loss from multi-step purification processes is lessened in the single-pot system, as is the risk of contamination, both advantages in large scale production. The major disadvantage of chemical capping on the large-scale is the availability of the raw materials, the capped nucleotide analogs, that must be produced at scale with the mRNA product. For enzymatic capping, the higher efficiencies lessen the impact of uncapped contaminants that must be removed. The multi-enzyme capping process is scalable via parallelization or continuous manufacturing. Ease of supply of the enzymes is the limiting factor for this process. Both chemical and enzymatic capping are well suited for single-use manufacturing systems, an advantage for enzymatic capping since there is no need for cleaning validation with single-use systems. Enzymatic capping has the additional advantage that the resulting naturally capped mRNA is a well known product to regulatory agencies, which will make it a more viable option for clinical use. Costs scale favorably for enzymatic capping since the cost of the enzymes is a smaller percentage of the overall costs for large production volumes.

Chemical capping provides a streamlined alternative to enzymatic approaches by enabling co-transcriptional 5' capping during IVT mRNA synthesis. Our chemical capping reagents are developed to support high capping efficiency, simplified workflows, and robust process control, making them well suited for both research and scaled mRNA production. Each system is optimized for compatibility with commonly used RNA polymerases and standard IVT conditions.

Our high-efficiency co-transcriptional capping systems are designed to achieve a high proportion of properly capped mRNA directly during IVT. By eliminating the need for post-transcriptional enzymatic steps, these reagents help reduce process complexity, shorten production timelines, and minimize variability. Efficient cap incorporation supports improved mRNA stability and translation efficiency, while maintaining reproducibility across batches.

For regulated and controlled manufacturing environments, we offer GMP-grade chemical capping reagents produced under strict quality systems. These reagents feature consistent composition, low impurity profiles, and comprehensive documentation, supporting reproducible performance and long-term process stability in mRNA production workflows.

Choosing between chemical and enzymatic capping depends on your priorities for efficiency, scalability, workflow simplicity, and process control, and the right strategy can significantly impact mRNA quality and yield. If you are evaluating or transitioning to chemical capping to improve IVT performance, our team can help you identify the most suitable solution—contact us today to discuss your capping strategy and request technical guidance or a quotation.

References:

Chemical capping occurs during IVT, while enzymatic capping is performed after transcription.

Chemical capping is generally easier to scale due to fewer processing steps.

Enzymatic capping can provide precise cap modification but adds process complexity.

Chemical capping often reduces time and handling costs in IVT workflows.

Yes, both methods can be efficient when properly optimized.