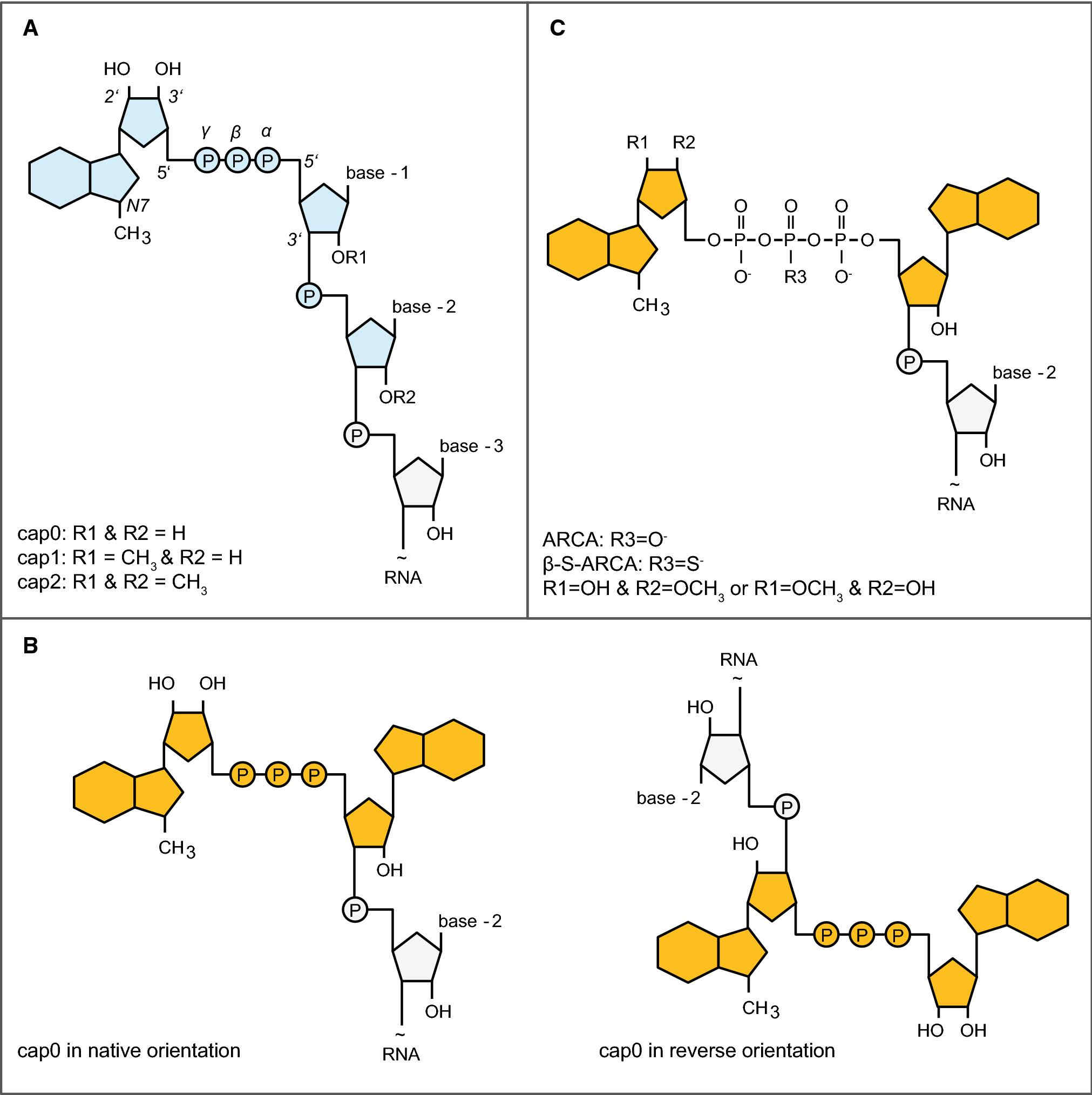

Cap analogs control the translational efficiency of IVT mRNA by influencing how well the 5' end is recognized by the translation initiation machinery. The chemical nature of a cap – its methylation status, phosphate number, and ribose modifications – sets the degree to which transcripts are fully capped, the degree to which they are inserted in the correct orientation, and its binding affinity to eIF4E. A cap with high affinity for eIF4E, quantitative incorporation, and resistance to reverse insertion will outcompete the natural m7GpppG by several-fold in rabbit reticulocyte lysate and most cell-free systems, as well as in most in-cell systems. Analogues with significant levels of backwards incorporation or rapid dissociation from eIF4E are competitive inhibitors and deplete the translatable mRNA pool. Overall, the net translation level is set by three independent factors, capping efficiency, orientation fidelity, and cap-eIF4E affinity, that can each be adjusted by atomic substitutions to the guanosine and triphosphate group.

Translation efficiency of IVT mRNA systems is the cumulative result of cap identity, 5'-UTR architecture, poly(A) tail length, and the ratio of initiation and decay determinants in the reaction system. A capped transcript, which is otherwise identical to its uncapped counterpart, can generate orders of magnitude more protein simply because the cap licenses recruitment of ribosomes and because it protects the message from 5'-exonucleases. However, that same cap structure will not necessarily act equivalently in wheat-germ extract, HeLa lysate, or electroporated dendritic cells, because each system has different concentrations of eIF4E, 4E-BPs, and decapping enzymes. Efficiency is therefore not an intrinsic constant of the mRNA, but a context-dependent probability of successful initiation per unit time.

Operationally, translation efficiency is defined as normalising the amount of reporter protein produced to the number of full-length mRNA molecules at the start of the experiment. In practice, this involves accounting for uncapped and degraded mRNA species that would otherwise contribute to the apparent protein output. The main parameters include the capping efficiency (fraction of transcripts capped with a functional analogue), orientation (fraction of capped species in which the cap analog is introduced in the 5'–3' orientation), eIF4E binding affinity (physiological salt conditions, Kd) and relative translation efficiency (normalised protein output relative to a known capped message). These parameters are not necessarily additive and instead contribute to protein output in a multiplicative fashion. A twofold increase in orientation, for example, could result in a 5-fold increase in overall protein levels in the presence of a modest increase in cap-binding affinity. By the same token, a cap analog that performs best in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate system may perform poorly in primary human cells if its phosphodiester backbone is a target for serum decapping enzymes. This is why orthogonal performance metrics in different expression systems is a key criterion in the clinical development process.

Table 1 Cap-Related Metrics and Typical Acceptable Ranges

| Metric | What It Measures | Common Determinant | Impact on Protein Output |

| Capping efficiency | Fraction capped | Polymerase selectivity | Linear up to plateau |

| Correct orientation | 5'–3' vs 3'–5' incorporation | Analog symmetry | Exponential when > 80 % |

| eIF4E affinity | Cap-initiation factor binding | N7 and ribose mods | Threshold dependent |

| Decapping resistance | Susceptibility to DCP1/2 | Phosphorothioate presence | Longevity multiplier |

Cap structure is the major factor, but several other upstream and downstream features fine-tune the ultimate output. First, secondary structure in the 5'-UTR represses initiation when strong hairpins hide the start codon; a strong cap can rescue this defect, at least partially, by recruiting more eIF4A-mediated unwinding activity. Second, the poly(A) tail has a cooperative effect with the cap: for example, a 110 nt tail can double the output relative to a 30 nt tail, and this enhancement is cap-analog dependent, because some of the analogs attenuate the interaction between PABP and eIF4G. Third, the ratio of cap analog to GTP during transcription determines the proportion of uncapped species; typically a 4-fold molar excess of analog is used, but phosphorothioate variants are much less efficient substrates for T7 RNA polymerase, and so they need a lower molar excess. Fourth, the salt composition of the translation lysate influences the apparent affinity between cap and eIF4E: physiological concentrations of K and Mg stabilize the closed high affinity conformation of eIF4E, whereas hypotonic buffer conditions instead drive eIF4E off of the cap. Fifth, the presence of decapping enzymes such as DCP1/2 decreases the effective half-life; phosphorothioate analogs with linkages at the β- or γ-phosphate are resistant to hydrolysis and so are available for multiple rounds of initiation. Taken together, these considerations show that cap analogs are the master dial, but that the cellular or lysate environment in which the message is translated tunes the ultimate output.

Cap analogs are the key that determines whether a given in-vitro transcript is accepted as a bona fide template for ribosome entry or discarded by the scanning machinery. The chemical signature of the analog (methylation status, phosphate substitutions, sugar modifications) sets the odds that eIF4E will dock, nucleate the eIF4F complex, and license the 40S subunit to scrutinize the 5' leader. A poorly recognized analog slows recruitment, heightens the chance that the message will be sequestered by 4E-BPs or decapping enzymes, and thereby reduces the number of initiation events per unit time. By contrast, an analog that binds eIF4E tightly and is resistant to enzymatic removal lengthens the time window during which the mRNA is "open for business" and allows repeated rounds of ribosome loading even when transcript concentration is limiting. The analog therefore acts as a gatekeeper: its intrinsic affinity for the cap-binding pocket is converted, through a chain of protein–protein contacts, into the rate at which the first peptide bond is formed.

The initial recruitment reaction occurs as the small subunit is escorted to the 5' end by a ternary complex that links eIF4E bound to the cap, eIF4G as a scaffold and eIF3 projecting contacts that dock the 40S platform. The length of time that this nascent assembly endures is determined by the cap analog decorating the transcript. If it is similar in structure to native m7GpppG, then eIF4E wraps around the methylated base, stacks tryptophan side chains against the guanine, and secures the triphosphate through electrostatic contacts; this clamp is not disrupted by other mRNAs or by inhibitory proteins. Following eIF4E binding, eIF4G folds into a structure that has exposed binding sites for eIF3 and the poly(A)-binding protein, so that the 5' and 3' ends of the message are joined into a closed loop. The 40S subunit, which is already loaded with initiator tRNA and GTP-eIF2, is positioned with its solvent-side surface facing the 5' leader. A cap analog that weakens any link in the chain (most often by reducing eIF4E residence time) causes the premature dissociation of the pre-initiation complex, which is then free to recycle: the 40S subunit must be released back into the cytosolic pool and wait for another encounter. In this way, the analog does not simply decorate the 5' end of the transcript; it establishes the kinetic lifetime of the entire recruitment intermediate, and thus how many 40S particles will be successfully handed off to the scanning step.

Table 2 Ribosome Recruitment

| Recruitment Stage | Key Analog-Dependent Event | Failure Phenotype |

| eIF4E docking | Stable π–π stacking with Trp residues | Rapid rebinding to competitor RNA |

| eIF4G recruitment | Formation of 5'–3' bridge | Loss of poly(A) synergy |

| 40S tethering | eIF3–eIF4G contact | Abortive scanning, 40S release |

The cap-binding pocket of eIF4E is a curved slot lined with conserved tryptophans that sandwich the methylated guanine, and a cluster of basic residues nearby that clasp the phosphates. Analogs bring small steric or electronic perturbations into this slot that are propagated in complex ways to modulate on-rate and off-rate without necessarily biasing the equilibrium constant in an intuitive direction. The single sulfur-for-oxygen substitution at the β-position for example packs in more van-der-Waals contacts and less hydration, extending residence time and indirectly strengthening association with eIF4G, whose binding site overlaps the lateral face of eIF4E. The same substitution can in principle attenuate recognition by decapping enzymes, so that the transcript remains long enough for multiple ribosomes to load. On the other hand, analogs that omit the N7-methyl group still fill the pocket but not trigger the closing motion of the tryptophan lid, leaving eIF4E in an open conformation that is susceptible to 4E-BP competition. Because 4E-BPs and eIF4G share a docking motif, any analog-induced destabilization that biases toward the former will repress translation even when overall cap affinity is modest. Downstream of eIF4E, the initiation factor eIF3 "senses" the stability of the eIF4E–eIF4G junction, so if the analog stabilizes this junction eIF3 transmits the signal to the 40S subunit by shifting its internal conformation, priming tRNA accommodation and speeding up GTP hydrolysis by eIF2. The chemical signature of the cap analog is thus transduced through at least three layers—direct contact with eIF4E, modulation of eIF4G affinity, and allosteric tuning of eIF3—before the ribosome ever encounters the start codon.

Cap analogs can differ in their methylation pattern, their phosphate modification, and the ribose they contain. These chemical variations at the atomic scale result in distinct phenotypes at the level of translation. A cap analog that sequesters eIF4E for an extended residence time, that can only be inserted in the correct orientation, and that is resistant to hydrolytic decapping will outcompete a different analog lacking any one of these features. The comparison, therefore, is made on three axes – orientation fidelity, stealth from the immune system, and kinetic stability – each a function of where methyl, thio, or methoxy groups are located on the guanosine and the first one or two nucleotides transcribed.

Cap 0 is modified with a single N7-methyl on the terminal guanosine while Cap 1 has a 2'-O-methyl added to the first transcribed ribose in addition. The methyl group serves as a protective mask against cytosolic sensors that evolved to detect foreign transcripts so Cap 1 is invisible to innate immunity and remains intact long enough for several rounds of translation. Critically, the 2'-O-methyl extends into the minor groove where eIF4E and 40S subunit interface and acts as a conformational brace on the closed form of the initiation complex, thereby speeding up recruitment. Cap 0, by contrast, is interpreted as non-self and the signal gets amplified into the nucleus and provokes interferon release, which ultimately phosphorylates eIF2α and throttles global protein synthesis. Even in cell-free lysates where this surveillance pathway is largely muted, Cap 1 outcompetes Cap 0 because the same 2'-O-methyl also blocks endonucleases that chew the 5' end, thereby prolonging the functional half-life of the message. The upshot is that Cap 1 reliably produces more full-length protein per microgram of input RNA without the translational shutdown that Cap 0 begets. At a structural level, the 2'-O-methyl forces the first nucleotide into a C3'-endo pucker that inverts the minor groove by ~0.5Å, a perturbation that is detected by a conserved arginine in the RNA-binding loop of eIF4E. The arginine swings into a transient cation–π interaction with the methyl group, introducing an enthalpic term that increases residence time without adding to the entropic penalty for immobilizing the cap. Cap 0 is missing this contact, so its off rate is set by the weaker phosphate and base interactions alone, which results in more frequent release and rebinding cycles. Each release is an opportunity for a competitor transcript to grab eIF4E, effectively lowering the concentration of initiation-competent complexes. The cumulative difference in rebinding events over the course of a typical one-hour lysate reaction becomes a large gap in protein output even if the initial binding constants are not that different. In intact cells, the gap widens because IFIT proteins bind to uncapped or Cap 0 mRNAs and sterically block eIF4E binding, a roadblock that is circumvented when the 2'-O-methyl is in place.

Table 3 Functional Comparison

| Comparison Axis | Key Chemical Determinant | Translational Consequence |

| Orientation fidelity | 3'-O-block on cap analog | Eliminates reverse inserts |

| Immune stealth | 2'-O-methyl on first nucleotide | Evades IFIT/RIG-I sensors |

| Kinetic stability | Phosphorothioate linkage | Resists DCP1/2 cleavage |

| Manufacturing fit | Dinucleotide vs enzyme substrate | Dictates cost and scalability |

Standard m7GpppG inserts at random in either orientation, so on average half of the transcripts carry the methylated guanosine internally, where it is unable to recruit eIF4E; these molecules are non-functional and compete for ribosomes. ARCA (anti-reverse cap analog) is blocked at the 3'-OH of the methylated guanosine, allowing insertion only in the correct orientation. As a result, every ARCA-capped transcript is potentially translatable and the lack of reverse insertions removes a large sink of non-functional mRNA. The practical consequence is that ARCA shifts the entire population toward translatable species, so the same mass of RNA produces more protein even when absolute capping efficiency is only marginally higher. The 3'-O-methyl substitution also lowers the off-rate from eIF4E, prolonging the residence time of the initiation complex and increasing the probability that a 40S subunit will complete scanning and find the start codon. Standard cap analogs, by contrast, must be used in four-fold molar excess over GTP to achieve only partial orientation correction, a condition that reduces full-length transcript yield and still leaves a substantial fraction of reverse-capped, non-functional molecules. The mechanistic advantage of ARCA is therefore more pronounced under conditions where transcript abundance is limiting, such as micro-injection into zygotes or electroporation into primary T-cells. In these settings, the fraction of functional mRNA directly determines the dose of antigen or therapeutic protein that can be achieved, so eliminating the 50 % waste inherent in standard capping translates into an effective doubling of the delivered dose without increasing RNA mass. ARCA also shows superior performance in lysates derived from organisms with stringent cap-recognition requirements, such as insects or plants, where the penalty for reverse insertion is even greater because internal m7G dinucleotides are recognized by decay factors that catalyze endonucleolytic cleavage. From a manufacturing perspective, the higher cost of ARCA is offset by the reduced need for post-transcriptional purification: because nearly every transcript is capped in the correct orientation, the population is homogeneous and behaves predictably in downstream assays.

Schematic representation of different cap structures.2,5

Schematic representation of different cap structures.2,5

Chemical capping adds the cap structure during IVT by adding a dinucleotide analog to the reaction mix. This one-step protocol shortens the manufacturing time and minimizes the risk of contamination from additional enzymes. However, its vulnerability is due to incomplete orientation and Cap 0 identity of most analogs. A separate 2'-O-methylation step would be required to produce Cap 1 if needed. Enzymatic capping is conducted post IVT using recombinant guanylyl-transferase and methyl-transferases and results in near-quantitative (>95%) Cap 1 modification independent of transcript length and free of uncapped species and reverse-oriented caps. In addition, the enzymatic workflow is compatible with phosphate-bridge modifications (e.g. phosphorothioates) that are not accepted by many polymerases. The enzymatic route allows for custom cap architectures that may have better resistance to decapping. The trade-off with enzymatic capping is the addition of several unit operations (buffer exchange and removal of nucleotides, dual-enzyme QC) that increase cost and the overall production time. Both approaches are generally accepted by regulatory authorities as long as a sufficiently high capping efficiency is demonstrated. However, for late stage candidates, sponsors are often choosing enzymatic capping as it is more likely to provide a consistent Cap 1 identity throughout multi-gram batches and its impurity profile is simpler. Co-transcriptional ARCA (hybrid approach) is sometimes used for early toxicology lots followed by switch-over to enzymatic Cap 1 for clinical scale, thus capitalizing on the speed of chemical capping for iterative dose selection early on and reserving the speed and reproducibility of enzymatic capping for late stage material.

In diverse, unrelated systems, cap analog identity has proven to be the most reproducibly significant factor affecting translational output, surpassing promoter activity, codon bias, or poly(A) tail length. In direct comparisons, parallel reactions bearing equivalent reporter open reading frames, samples containing high-affinity caps disproportionately produce more intact protein per microgram of starting RNA, have increased functional half-lives, and elicit reduced innate-immune responses. The following sections weave together some representative data sets from cell-free lysates and whole mammalian cells to show how cap-related factors manifest through each experimental stratum.

Translation in rabbit reticulocyte, wheat germ or reprogrammed E. coli lysate each represent a quantifiable complement of initiation factors, allowing the contribution of the cap to be decoupled from later events in the cell. When reticulocyte lysate is supplemented with luciferase mRNA possessing Cap 0 or Cap 1, linear product accumulation by the Cap 1 template is sustained for >2 hours, while that by Cap 0 stalls after 1 hour coincident with detection of eIF2α phosphorylation. Replacing the native m7GpppG with an anti-reverse cap analog (ARCA) further extends the linear phase because reverse-inserted molecules—translationally inactive competitors—are eliminated; the same mass of RNA thus yields more protein without adding lysate volume or incubation time. Reticulocyte systems also model how cap stability can play a role in the context of 5'-UTR architecture. Insertion of a moderately stable stem-loop directly downstream of the start codon decreases yield by two-fold when the transcript is capped with m7GpppG, yet the same structure is tolerated when a phosphorothioate-stabilized ARCA is used, implying that prolonged eIF4E residence overcomes the energy barrier of unwinding. In wheat-germ extract, where eIF4E is less abundant, the penalty by Cap 0 is more severe, suggesting that plants may depend more on the 2'-O-methyl mark for cap recognition. Bacterial cell-free systems (E. coli or Vibrio natriegens) have no eIF4E, yet cap-dependent effects can be measured when the RNA is programmed into hybrid platforms containing purified mammalian initiation factors. Only correctly orientated Cap 1 transcripts form 48 S pre-initiation complexes that are detectable by toe-printing under such chimeric conditions, highlighting that the cap quality determines the very first interaction between mRNA and ribosome even in a foreign proteome.

Electroporation of the same capped mRNAs into primary human fibroblasts or immortalized CHO lines recapitulates the qualitative ranking seen in lysates, although additional layers modulate the final protein yield. Cap 1 transcripts are detected at higher levels for over 24 h, while Cap 0 messages decay by 6 h with coincident RIG-I activation and IFN-β secretion. The addition of ARCA extends expression by decreasing the number of reverse-capped decoy transcripts competing for the limiting eIF4E. The cap advantage is greatest at low RNA doses: when microgram levels are used, the cellular cap-binding protein becomes saturated and the differences between analogs shrink, as expected for a mass-action model in which affinity only matters when the factor is limiting. Single-cell imaging of cap 0 versus cap 1 indicates that the longer half-life conferred by high-affinity caps translates into a broader distribution of intracellular fluorescence. This indicates that individual cells translate for longer time windows, rather than initiating translation more quickly. Flow-cytometric sorting followed by RT-qPCR indicates that the high-fluorescence sub-population contains full-length message while the dim cells have been truncated 5'-end, confirming that cap stability protects against exonucleolytic erosion rather than enhancing early initiation events. In dendritic cells that are induced to mature with LPS, the Cap 1 mRNA not only produces more reporter, but also matures the cells less aggressively, as measured by surface CD80 and CD86 levels. This implies that immune stealth and translational output are coupled phenotypes that can be traced to the same methyl group. Finally, when the mRNAs are formulated into lipid nanoparticles and delivered by IV injection to mice, the plasma concentration of secreted nano-luciferase is dependent on cap type, indicating that the in-vitro hierarchy survives formulation, circulation, and endosomal release steps.

Translation efficiency in in vitro transcribed (IVT) mRNA is strongly influenced by the structure and quality of the 5' cap, as well as the consistency of cap incorporation during transcription. Our cap analogs are specifically optimized to support efficient translation initiation, enabling reliable ribosome recruitment and robust protein expression across a wide range of IVT systems. Each product is developed with careful attention to chemical purity, cap orientation, and workflow compatibility to ensure predictable translation outcomes.

Our cap analogs have demonstrated consistent and reproducible performance in IVT mRNA systems, supporting high levels of protein expression in both cell-free and cell-based translation models. Efficient cap incorporation promotes effective interaction with cap-binding proteins and translation initiation factors, resulting in improved translation efficiency and reduced variability between experiments. These performance characteristics make our cap analogs well suited for mRNA optimization and expression studies.

Reliable translation efficiency depends on consistent raw material quality. Our cap analogs are manufactured under tightly controlled conditions and subjected to rigorous analytical testing to ensure batch-to-batch consistency. Key quality attributes such as purity, structural integrity, and impurity profiles are carefully monitored, helping maintain stable IVT performance and reproducible protein expression across repeated mRNA production runs.

Achieving high protein expression from IVT mRNA requires careful optimization of capping strategy and cap analog selection, as even small variations can significantly impact translation efficiency. If you are aiming to maximize protein output and improve reproducibility in your mRNA workflow, our optimized cap analog solutions can help—contact us today to discuss your application and request technical support or a quotation.

References

Cap analogs determine how effectively mRNA recruits ribosomes and initiates translation.

Yes, cap structure and orientation directly impact protein expression levels.

ARCA and Cap 1 analogs are often associated with improved translation efficiency.

Yes, inconsistent cap quality can lead to variable translation outcomes.

Yes, cap analog optimization is a key step in improving IVT mRNA performance.