Protecting groups transform the ribose–base–phosphate framework into a programmable synthon with only one exposed reactive center, which is revealed when and where the chemist wishes. Temporarily masking all nucleophilic or acidic functionalities except the 3'-phosphoramidite, protecting groups prevent branching, depurination and phosphate isomerization, while permitting iterative acid–base–redox cycles to proceed at near-quantitative yield. The result is a solid-phase assembly line that can append 30 or more nucleotides with single-base accuracy, to deliver therapeutic sequences whose potency, safety and manufacturability are determined at the monomer stage.

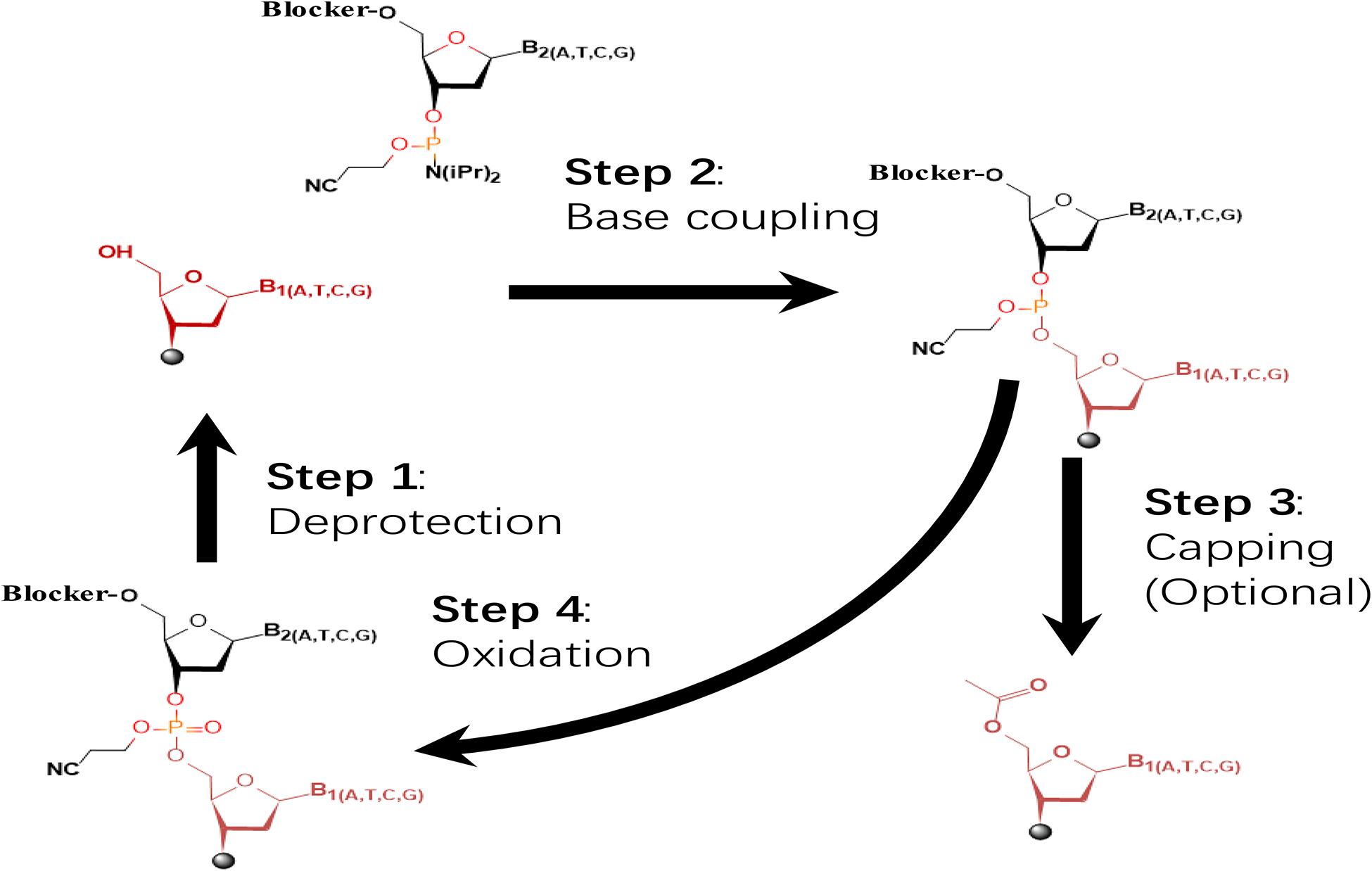

Fig. 1 The dominating four-step, phosphoramidite chemistry widely applied in commercial oligo synthesizers.1,5

Fig. 1 The dominating four-step, phosphoramidite chemistry widely applied in commercial oligo synthesizers.1,5

Therapeutic oligonucleotides must be synthesized to their genomic address with zero tolerance for error. Shift a therapeutic oligonucleotide one base and it will silence the wrong exon or encode a dominant-negative splice product. For this reason solid phase phosphoramidite chemistry is applied with semi-conductor level tolerances in which every coupling cycle must be >98 % site-selective in dozens of consecutive iterations. This fidelity is not possible without orthogonal protecting ensembles that render all functional groups inert except the single hydroxyl which is to react.

Mismatch to a single base in the seed region (positions 2–8) of the guide strand of an siRNA can reprogram RISC to cleave hundreds of off-target mRNAs, resulting in unintended gene silencing and potential toxicity. Likewise, a single mismatch in an antisense gapmer can either abolish RNase-H recruitment or alter splice-site selection, potentially turning a therapeutic molecule into a disease-causing allele. Hence regulatory agencies consider the published sequence to be part of the active substance specification; any change mandates repeat tox studies and bridging of stability, making base-level fidelity a quality attribute requirement rather than an academic ideal.

Four chemical stresses are applied per elongation cycle: acid detritylation, tetrazole phosphoramidite activation, acetic anhydride capping/iodine oxidation. Reagents are applied to a swollen resin whose micro-environment can trap reagents and exaggerate local pH excursions. 30+ such stresses accumulate in full cycles so even 1 % side reaction per step leads to a crude mixture that is heterogenous and dominated by truncated/branched sequences. Complications are increased by solvent changes, moisture ingress and temperature gradients within large column scales, and so protecting groups must remain inert through the entire stress envelope and yet be removable cleanly on deprotection.

5'-O-DMT ethers are transient gates that open only in acid to make certain that only the terminal hydroxyl is extended and that none of the internal phosphates or base amines are unmasked. Base-labile amides (benzoyl, isobutyryl) protect nucleobase amines from acylation during capping. The fluoride-labile β-cyanoethyl group on phosphate endures oxidation but is removed in mild ammonia. The temporal choreography transforms a polyfunctional molecule into a single-reaction synthon and lets automated synthesizers repeat detritylation, coupling, capping and oxidation without cumulative damage, so that the final crude product needs only one or two polishing steps to reach clinical purity specifications.

Table 1 Protecting-group duties across the solid-phase cycle

| Cycle Step | Chemical Stress | Protecting Role | Risk if Mask Fails |

| Detritylation | 2 % acid | 5'-DMT only | Premature loss → branching |

| Coupling | Tetrazole activation | All others stay on | Base deprotection → acylation |

| Capping | Ac2O/pyridine | Amines remain masked | Free NH2 → chain termination |

| Oxidation | I2/H2O/pyridine | Phosphate mask endures | β-CE loss → diester hydrolysis |

Oligonucleotide synthesis can thus be viewed as a choreographed dance through a minefield of nucleophiles, electrophiles and protic sites. Each nucleoside has a 5'-OH, a 3'-OH, exocyclic base amines and a phosphate precursor, all of which can compete for the same activating reagents. If each of these groups is not masked in a disciplined manner the chain would branch, truncate or mutate within the first coupling cycle and solid phase elongation would be impossible at scale. The entire phosphoramidite protocol therefore relies on a strategy of rendering every reactive group inert except the single hydroxyl meant to react. This converts a polyfunctional scaffold into a programmable monomer.

Unmodified adenosine alone has three distinct nucleophiles, the 5'-primary hydroxyl, the 3'-secondary hydroxyl and the exocyclic N6 amine, each with different pKa and steric environment. In the presence of phosphoramidite activators these sites can be phosphorylated at random, leading to branched "fork" structures where the same base is tethered to two phosphate backbones simultaneously. Guanine and cytosine add further complexity via N2 and N4 amines that can undergo transamidation during base-catalysed deprotection, while the 2'-OH in RNA is an internal nucleophile that promotes strand scission under physiological magnesium concentrations. The density of such reactive handles means that selectivity cannot be achieved by stoichiometry alone; instead, orthogonal protecting ensembles must silence every undesired site while preserving the reactivity of the 3'-OH destined for chain extension.

In the absence of base-protecting amides, acetic anhydride capping reagents acylate exocyclic amines, which results in N-acetyl adducts that distort base-pair geometry and are recalcitrant to global deprotection, creating mutagenic transcripts that co-elute with the full-length product. Unprotected 5'-hydroxyls can attack activated phosphoramidites, leading to double-length "n + 0" inserts that plug purification resins and decrease overall yield. Perhaps most insidious is 2'-OH-mediated transesterification in RNA chemistry: under the mildly basic conditions used for oxidation, the 2'-oxygen can attack the adjacent phosphate, generating a 2',3'-cyclic phosphodiester that fragments the backbone and appears as a late-eluting impurity indistinguishable from a deletion sequence by routine LC-MS. These side reactions are not academic curiosities; they scale with reactor volume and can transform a seemingly robust route into a validation nightmare once multi-kilogram campaigns begin.

Selective chain growth thus requires that only the 3'-OH react with the incoming amidite, while the other nucleophiles are all invisible to the procedures of acid detritylation/tetrazole activation/capping and oxidation. This is done by using protecting groups with compatible "lability windows" – acid-labile DMT for the 5'-OH, base-labile amides for the base amines, fluoride-labile silyls for the 2'-OH, and a phosphate mask that is stable to oxidation, but cleaves in mild ammonia. In this way, each protecting group serves as a molecular "valve" that only opens in response to a specific stimulus, ensuring that the activated phosphoramidite can react with only one nucleophile per cycle. Otherwise, a chromatographic "rescue" step is needed, which not only sacrifices yield but also introduces a second class of solvents to the waste-treat system, explaining why protecting-group strategy is considered a "process parameter" rather than a convenience.

Table 2 Side-reaction landscape in unprotected nucleoside chemistry.

| Unprotected Site | Typical Side Product | Downstream Impact | Masking Solution |

| Base –NH2 | N-acetyl adduct | Mutagenic transcript | Benzoyl/iBu amide |

| 5'-OH | Double insertion (n + 0) | Length heterogeneity | DMT ether |

| 2'-OH (RNA) | 2',3'-cyclic phosphate | Strand scission | TBDMS/TOM ether |

| 3'-OH premature | Self-coupling dimer | Aggregation, filter clog | Temporary silyl block |

Solid-phase oligonucleotide synthesis involves a repeated cycle of four steps (detritylation, coupling, capping, and oxidation) and controlling the reactivity of hydroxyl and amine functional groups by using protecting groups that are stable during the coupling and capping steps but can be removed during detritylation. Three protecting groups with different lability periods have been used. For example, an acid labile protecting group for the 5'-OH (such as a dimethoxytrityl ether), stable amine protecting groups for the nucleobase amines (such as benzoyl or phenoxyacetyl amides), and a phosphate protecting group that is stable to oxidation but removed under mild conditions of ammonia.

The 5'-dimethoxytrityl (DMT) ether serves as a temporary protective group: it is removed in seconds by 2–3 % dichloroacetic acid to unmask the terminal hydroxyl, but it is stable to the mildly basic conditions of the subsequent oxidation step after coupling. Its lipophilicity serves as a colorimetric signal: the orange cation is monitored in real time to determine the completeness of detritylation—its bulk also sterically protects against premature coupling during resin storage. As DMT cleavage is diffusion-limited, large-scale columns use a pulsed acid flow to avoid local over-exposure which could lead to depurination or premature 2'-deprotection for RNA substrates.

Exocyclic amines of A, C and G are derivatized into carboxamides (benzoyl, isobutyryl, acetyl) that are stable to the acidic detritylation and oxidative conditions but that cleave away from the oligonucleotide under concentrated aqueous ammonia in the global deprotection step. These protections prevent N-acylation by capping reagents and also block base-mediated transamidation that would produce mutagenic adducts co-eluting with the intact strand. The selection of acyl group can be tuned for electronic stability: the extra steric bulk of isobutyryl masks guanine N2 against O6-alkylation side reactions, and phenoxyacetyl versions permit ultra-mild ammonolysis for base-sensitive conjugates.

Temporary masks (DMT, silyl) are cleaved during the synthesis cycle itself, while permanent groups (base amides, β-cyanoethyl phosphate) remain intact until final global cleavage. Mis-classification is expensive: e.g. retaining DMT through ammonia treatment results in irreversible capping of the 5'-end, while premature loss of a base amide leads to acylation and sequence mutation. The design therefore correlates lability with function – acid-labile for 5'-OH, base-labile for nucleobase, fluoride-labile for 2'-OH – so that each protecting group disappears only when its protective function is complete, and never while downstream chemistry is still required.

Orthogonal refers to the use of different protecting groups that respond to different cleavage triggers (acid/base, fluoride/light) so that only one protecting group or "mask" can be removed at a time, with all other masks remaining on the molecule. If the protections were not orthogonal, then removal of one protecting group would lead to the removal of others. Therefore, this would result in the loss of sequence information, since branching, depurination, and phosphate migration would occur prematurely.

Orthogonal protection means that each protecting group has been selected for its unique lability window: acid-labile DMT for 5'-OH, base-stable amides for base amines, fluoride-labile silyls for 2'-OH, and a phosphate mask that can survive oxidation, but cleaves in mild ammonia. As each group is then removed without affecting the other groups, each ensemble is impervious to the conditions used to remove the others. The synthetic timeline thus becomes a programmable sequence of events instead of a random demolition. The idea is borrowed from peptide chemistry, but is more stringent in this context because the same molecule must be made to survive dozens of acid–base–redox cycles without cumulative damage.

The timing is strict: a short acid treatment takes away the DMT in seconds, but not the base-labile amides nor the phosphate β-cyanoethyl groups; a concentrated ammonia treatment depletes the latter two, but not the silyl ethers, which stand up to the attack until the last step, the fluoride treatment. Photo-labile (ortho-nitrobenzyl) alternatives can be used for additional selectivity to pattern in space or to do extremely mild cleavage in the presence of base-labile conjugates. Mistiming these non-overlapping conditions leads to early deprotection events that introduce truncated or branched impurities that cannot be removed by chromatography.

Since each deprotection step is quantitative and site-specific, the growing strand remains in the desired sequence register (i.e. no off-pathway hydroxyls are exposed that could take the next activated amidite out of order). Orthogonality thus directly controls the final full-length yield and the absence of single-base deletions or insertions that would otherwise necessitate costly preparative HPLC rescue. Regulatory specifications treat the declared sequence as part of the active substance; orthogonality is therefore validated as a critical process parameter, with forced-spiking studies showing that even a 50 % overdose of cleavage reagent does not compromise protecting-group integrity at adjacent sites.

The kinetics, efficiency and reliability of each phosphoramidite coupling step is influenced less by the underlying nucleobase sequence than by the steric/electronic environment imposed by protecting groups. An appropriately designed mask will restrict rotational freedom around the 3'-hydroxyl, facilitate tetrazole-mediated activation and protect the phosphorus center from competitive attack by water or base amines. An ill-fitting protecting group ensemble may instead bury the reactive hydroxyl behind a lipophilic wall, slow activation kinetics and result in the exponential accumulation of truncated chains over thirty-odd cycles.

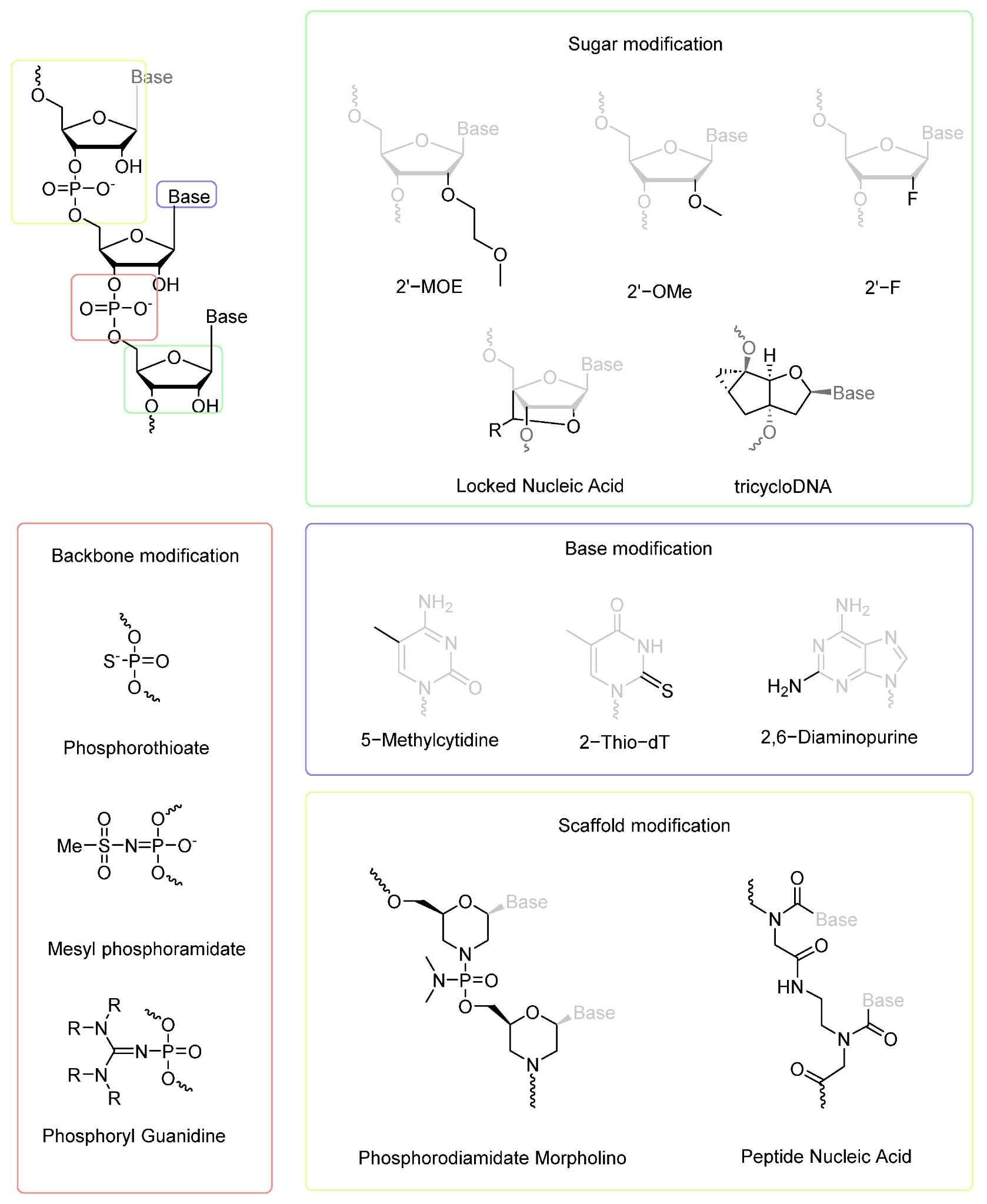

Bulkier 2'-O-TBDMS or 2'-MOE substituents may clash with activated phosphoramidite and make its approach to 5'-hydroxyl sterically disfavoured, especially in G-rich tracts that pre-organise secondary structure to a greater extent; in this case, smaller 2'-fluoro substituents or more nucleophilic activators (such as BMT) can offset the steric penalty without compromising stability. Electron-withdrawing protecting groups on the base (benzoyl, isobutyryl) lower the local pKa of neighbouring hydroxyls, slightly increasing the rate of proton transfer during tetrazole activation and shifting the equilibrium towards phosphite triester formation. Reaction engineering thus also couples activator choice to protecting-group sterics: while a 2'-F/Me blended strand can be coupled in seconds with standard tetrazole, a fully 2'-MOE segment may need longer recycle times or substituted tetrazoles to achieve the >99 % per-cycle yield needed for long oligos.

Truncation can also be caused when the 5'-OH is sterically inaccessible, or when it is temporarily masked by an acid-labile group that is too slow to cleave, leaving a population of unextended chains. This is reduced by the careful choice of protecting groups to give a consistent steric profile across all building blocks: the bulk of DMT protects against aggregation-induced masking, and base amides keep the nucleobase planar to avoid groove-collapse that can bury the terminal hydroxyl. Orthogonality also suppresses truncation, since early loss of a base or phosphate mask doesn't generate a new nucleophile that competes with amidite (averting "n − 1" peaks that require ion-exchange polishing downstream, which is expensive).

Fully automated synthesizers demand that each well in a 96-plates proceeds at the same flow rate and contact time. Protecting groups must therefore have identical kinetics in spite of slight differences in resin swelling or activator age. Sturdy masks like 2'-TBDMS or 5'-DMT do not suffer in this respect, but labile alternatives (e.g. the photo-cleavable o-nitrobenzyl group) could cause well-to-well variation if the UV dose slightly drifts. It is also desirable to use protecting groups which produce a visible by-product to standardize progress. For example, the orange cation formed by DMT can be quantified at 498 nm, and the real-time readout of coupling efficiency can be used to selectively activate double-coupling where necessary, rather than wasting reagents across an entire deck of resins.

A robust protecting-group strategy transforms the multi-step, multi-functional oligonucleotide pathway into a deterministic, flow-compatible process whose rate-limiting steps are no longer chemical side reactions but engineering parameters: resin swelling, solvent recovery and cycle time. By preemptively eliminating truncated sequences and diastereomeric impurities, orthogonal masks lighten the load on downstream ion-exchange and desalting columns, allowing campaigns to scale from grams to kilograms without a corresponding expansion of purification skid volume or solvent load. The outcome is a manufacturing template analogous to the logic followed for pharmaceutical small molecules: lock the impurity profile at the monomer stage, then scale reactor volume and flow rate while keeping critical quality attributes fixed.

Orthogonal protecting groups avoid branched "n + 0" inserts, base-acetylated adducts and 2',3'-cyclic phosphate scission fragments that co-elute with the full-length strand and that would otherwise require gradient-intensive HPLC to resolve. Since each side reaction is suppressed as it would normally occur, the crude product of solid-phase synthesis contains predominantly the desired sequence plus simple failure sequences (n − 1, n − 2) that can be polished by one or two ion-exchange passes rather than multi-column orthogonal purification. This simplification translates directly into plant throughput: the same preparative column that processes 100 g of well-protected crude can handle 10 kg without adding resin volume, shortening overall plant time and solvent disposal costs.

Temperature- and moisture-excursion tolerant protecting groups ensure that coupling efficiency is invariant as synthesis scales from 10 mmol glass columns to 800 mm stainless-steel reactors with radial thermal gradients. Cleavage kinetics for masks such as 5'-DMT and base-benzoyl amides are identical whether the acid front impinges as a gentle drip or a pulsed turbulent flow, so stepwise yield plateaus are scalable and predictable. This removes the need for batch-specific re-optimisation and enables statistical process control to be applied to critical attributes such as full-length percentage and residual solvent profile, turning each new batch into a predictable extension of the validation data set rather than a regulatory deviation.

Large column size allows higher linear velocities and longer contact times. These conditions magnify any protecting-group instability into detectable impurity buildup. Masks that can withstand the mechanical forces remain intact, and the same flow protocols used in a pilot-scale synthesizer can be implemented in ton-scale skid without further validation. The lighter impurity load also minimizes resin fouling, which lengthens column lifetime and allows for continuous-flow or carousel-type synthesizers that run multiple campaigns on the same packed bed. The result is a scalable platform where throughput is limited only by solvent logistics and activator supply rather than by chemical side reactions that scale with reactor volume.

The selection of a protecting group is a complex optimisation problem between several competing factors: their chemical stability and their ease of removal, their steric bulk and solubility, and their cost and their precedent in the industry. It should be stable enough to survive a series of acid/base and redox conditions, and then be removed without affecting the phosphodiester backbone, the modified sugars and any attached lipids. Early decisions in selecting a group that does not crystallise well, that cleaves too early, or that requires a very specific cleavage reagent will lead to late stage validation failures, resulting in an expensive re-design of the synthesis route when the intermediate is already available in kilograms.

Acid-labile 5'-DMT ethers need to survive multiple dichloroacetic acid pulses without forming depurination-prone N-acylated purines, and base-labile benzoyl amides need to survive the mildly oxidative iodine/pyridine bath for phosphate oxidation. Fluoride-labile 2'-silyl groups need to survive both acid and base pulses, a constraint that compels the designers to forego over-fluorinated solvents, which prematurely cleave Si–O bonds. Robustness is confirmed with forced-degradation studies, in which protected monomers are incubated at an elevated temperature under the harshest coupling cocktail; if any new peak emerges above the genotoxic qualification threshold, a protecting-group change is triggered before the route is freeze-framed under change-control.

Detachment is generally carried out at room temperature with concentrated aqueous ammonia. Therefore, the deprotection conditions must completely deprotect within these conditions leaving no hydrophobic amide or silyl residues that co-precipitate with the fully deprotected oligonucleotide and cause fouling of ion-exchange resins used in the next step. Milder alternatives, such as tert-butylamine/ethanol for base-labile conjugates and fluoride/acetic acid for only silyl removals, are becoming more widely used but require a mask whose lability is matched to the new reagent (e.g. phenoxyacetyl amides that hydrolyse in a few hours at 25 °C). Partial deprotection leaves "scarred" strands with residual acyl or silyl adducts that change the kinetics of hybridisation and may be undetectable by routine LC-MS analysis, thus requiring the developer to also validate a secondary orthogonal assay for low-level protecting-group byproducts.

2'-MOE, 2'-fluoro or 2'-O-methyl sugars, by their very nature, have a lipophilic substituent. The addition of a bulky benzoyl on the base pushes the protected monomer out of solubility in acetonitrile, which results in slow phosphitylation and filter-blocking precipitates in the synthesizer. This has led to the strategy of coupling smaller acyl masks (acetyl) to bulky sugars, or of using more polar silyl ethers (TOM) with improved organic solubility that are still fluoride-labile. In the opposite case where the base bears a conjugated lipid or fluorescent dye, the protecting group must be removable under conditions that do not hydrolyse the ester or amide linkages of the payload. Photo-labile or enzymatically removable masks are often needed, which take the system outside the classical acid/base/ammonia trilogy.

Table 3 Protecting-group decision matrix for modified nucleosides

| Modification Type | Preferred Base Mask | Preferred 2'-Mask | Cleavage Strategy | Risk if Mismatched |

| 2'-MOE | Acetyl | TOM | Fluoride/acetic acid | Precipitation with Bz |

| 2'-F | Benzoyl | TBDMS | Ammonia | Slower deprotection |

| Lipid-conjugate | t-Bu-phenoxyacetyl | TBDMS | Ultra-mild ammonia | Ester hydrolysis |

| Fluorescent dye | Photo-labile | TOM | 365 nm UV | Dye photobleaching |

Fig. 2 Examples of chemical modifications used to improve the therapeutic activity of oligonucleotides.2,5

Fig. 2 Examples of chemical modifications used to improve the therapeutic activity of oligonucleotides.2,5

We provide comprehensive expertise in protected nucleoside monomers and oligonucleotide synthesis process support, helping customers achieve precise sequence assembly, high coupling efficiency, and reproducible manufacturing performance. By combining optimized protection strategies with high-quality raw materials and technical guidance, we support efficient oligonucleotide production from early development through commercial manufacturing.

Our protected nucleoside monomers are designed using optimized, orthogonal protecting group strategies that enable selective activation and deprotection at each step of solid-phase oligonucleotide synthesis. These strategies ensure controlled reactivity of hydroxyl and base functional groups, which is critical for achieving single-base precision in complex oligonucleotide sequences. Our protecting group designs are compatible with both RNA and DNA synthesis workflows, including sequences incorporating modified nucleosides. By enabling clean, predictable deprotection cycles, these strategies help minimize side reactions, reduce truncated sequences, and improve overall synthesis efficiency.

We manufacture high-purity protected nucleoside monomers under stringent quality controls to ensure consistent performance in oligonucleotide synthesis. Each monomer is produced with tight control over impurity profiles, moisture content, and chemical stability, which are essential for reliable coupling reactions and reproducible results. High-purity protected monomers contribute directly to higher coupling yields, improved sequence fidelity, and simplified downstream purification, making them suitable for both development-scale synthesis and large-scale manufacturing.

For programs with specialized synthesis requirements, we offer custom protection design and process optimization services. Our technical team works closely with customers to develop tailored protecting group strategies, optimize coupling and deprotection conditions, and mitigate impurity formation. By integrating protection design with process development, we help ensure that custom protected nucleoside monomers are robust, scalable, and aligned with long-term manufacturing needs. This proactive approach reduces technical risk and supports efficient progression from early-stage research to clinical production.

We support oligonucleotide programs across the full development lifecycle, from early R&D to GMP manufacturing. Our flexible supply capabilities and technical expertise enable smooth transitions between development stages while maintaining consistent raw material quality and process performance. Materials are supported by appropriate documentation, traceability, and quality systems to meet regulatory expectations, helping customers maintain compliance and confidence as programs advance toward commercialization.

If you are looking to optimize oligonucleotide chain assembly through advanced protecting group strategies, our team is ready to help. Contact us today to discuss your synthesis challenges, request technical data or samples, or explore customized protected monomer and process support solutions tailored to your oligonucleotide manufacturing goals.

References

They ensure only one reactive site participates per step.

A strategy allowing selective deprotection without cross-reactivity.

Yes, they enable reliable automated solid-phase synthesis.

Yes, it increases truncation and impurity formation.

Core strategies are standardized, but optimized per modification.